Womb House Books Review: July 2024

Issue Two: Emma Copley Eisenberg on her debut novel, Housemates, “What I’m Not Reading” with Millions editor Sophia Stewart, and an essay from Emily van Duyne on Loving Sylvia Plath and J.D. Vance.

We have just celebrated our first month anniversary in our new brick-and-mortar space in Temescal Alley, Oakland. It’s been busy and exhausting in the best way possible. Thank you to everyone for their patience and support.

In our second issue of the WHB Review, we have an interview with Emma Copley Eisenberg on her debut novel, Housemates, “What I’m Not Reading” with Millions editor Sophia Stewart, and an essay from Emily van Duyne on Medea and Sylvia Plath inspired by her new book, Loving Sylvia Plath.

A beloved bookshop, East Bay Booksellers, suffered a terrible fire yesterday morning and are asking for help to rebuild. Donate to the cause if you’re able!

Subscribe for more books coverage and announcements from Womb House Books!

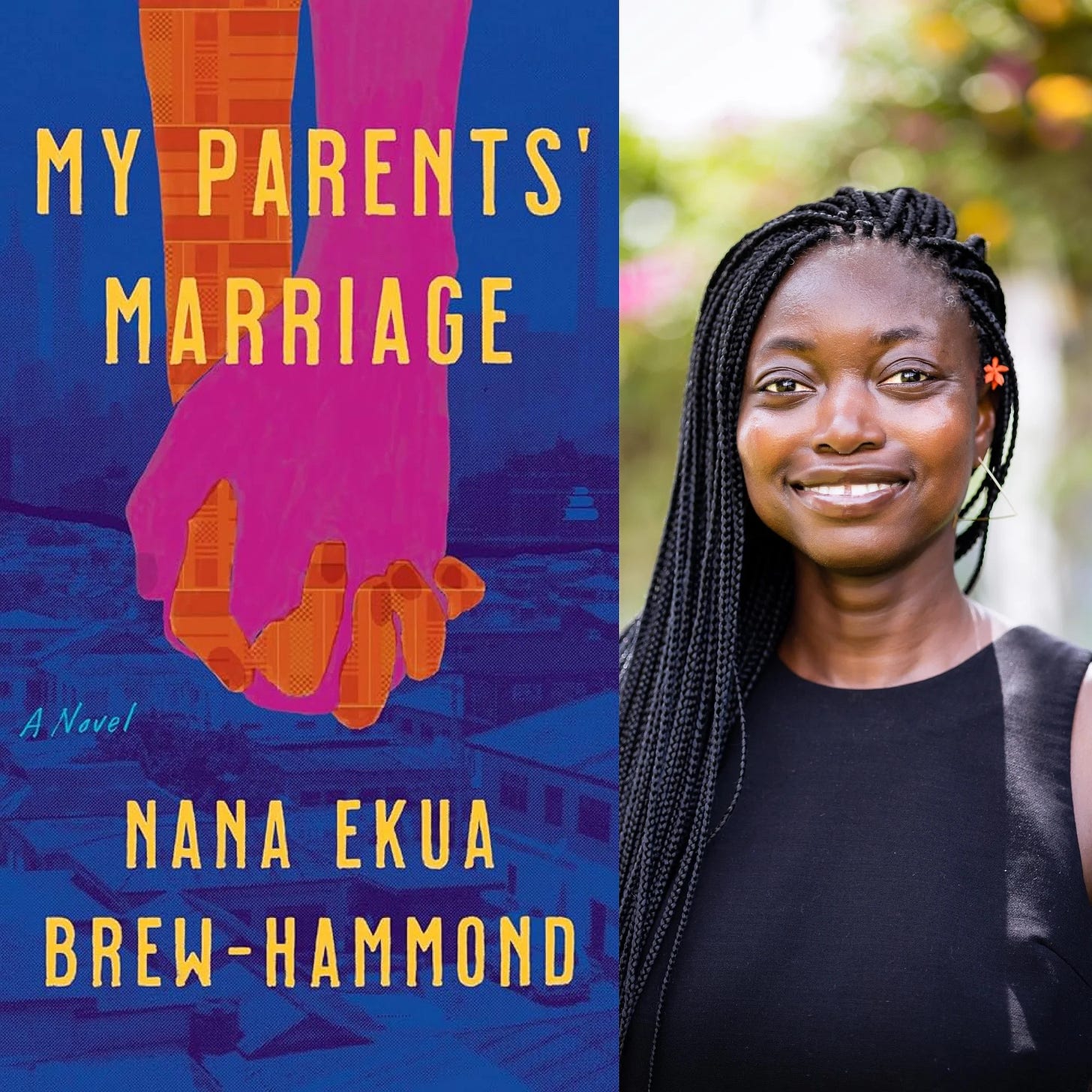

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond: My Parents’ Marriage

We are thrilled to host Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond at our Oakland shop to celebrate the publication of her debut novel, My Parents’ Marriage. Please join us on Thursday, August 22nd at 7pm. Nana will be discussing the book with Kyla Kupferstein Torres and signing copies.

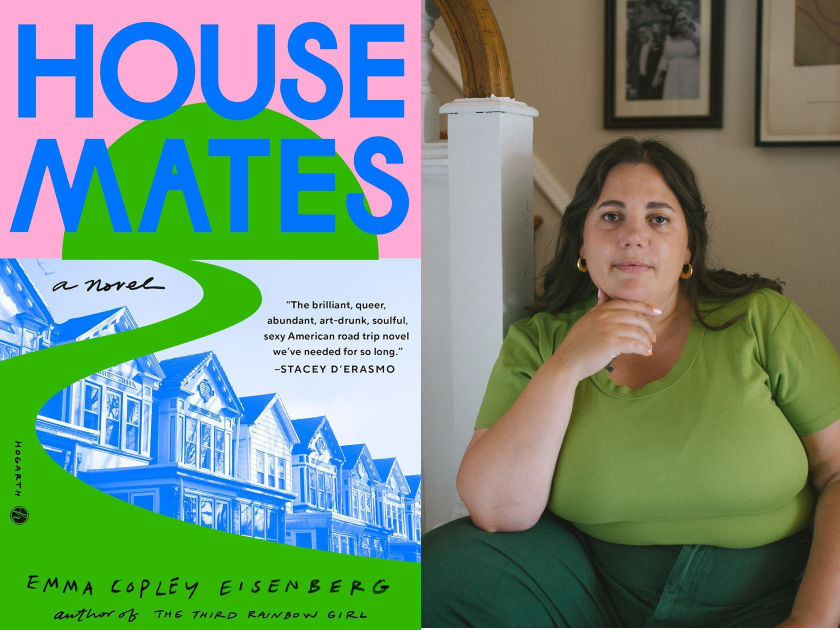

The Erotics of Being Seen: Emily Copley Eisenberg’s Housemates

Emma Copley Eisenberg’s debut novel, Housemates, is a bestseller at Womb House Books. The novel tells the story of Bernie and Leah, housemates in Philadelphia who embark on a road trip when both are feeling lost. Through working on their art together, and watching each other struggle to make art, their values and goals and shared joy become clearer. —Jessica Ferri

JF: I absolutely loved the scenes when Bernie and Leah are validating each other and themselves by watching and looking at each other working, more specifically when Leah looks at Bernie while she's taking pictures, and how they both feel seen. I think there's an erotics of seeing in this book. Can you say more about this?

ECE: Well put. A friend of mine said they think Housemates is a novel about falling in love with how someone else sees the world, and I think that's really true. To be "seen" has a double meaning in common parlance now—to be sighted/looked at, but also to be deeply understood, witnessed. One of the tensions in Housemates is how often we are looked at by those who don't understand us and how rarely we are looked at by the people who really do. To have your aesthetic form, your body appreciated in someone's eyes and have that person truly witness you is a thing that comes so rarely in this life. Bernie and Leah do both for each other, and they also turn this special double seeing on the people and places they come in contact with on their road trip, which is, of course, it's own kind of love.

JF: How did the writing process differ with Housemates from your first book? How has the publication process been different, if at all?

ECE: Oy vey! So different. I got my MFA in fiction and always thought my debut would be fiction but different projects demand different forms and mature at different speeds, and the urgency of the political moment in 2016 seemed to demand nonfiction—I just felt I could not go in my fiction writer's room and close the door on the world.

My first book, The Third Rainbow Girl, was extremely difficult to write and demanded an enormous amount of reporting and research so publishing it was a joyful and excruciating process implicating big questions of ethics, class, privilege, and positionality. All the while I was writing and promoting TTRG, I was still writing fiction, first short stories and then the pages that would become Housemates. And something fascinating happened which was that by leaving fiction temporarily, I found my way back to it. I remembered why I had loved fiction in the first place—the expansiveness and the play and the big questions that only fiction allows. The publishing process for Housemates was sweeter and more personal in a strange way, with so many readers reaching out to say how much they loved this story and these people that came from my mind.

JF: Can you say more about the title? "Housemates" signals a queer relationship that wasn't safe to be open—lesbians or queer people calling each other their roommate or housemate in a hostile environment/society.

ECE: For sure, the title definitely has that layer. I also meant it as a way to center how the word "housemate" is kind of a catch all for all the domestic intimacies that really matter but that we as a society don't know have a label for—roommates in a shared house, lovers we co-habitated with, house guests, people we met at residencies or boarding houses or hotels who changed our lives but might not be around forever. These uncategorizable relationships are very queer to me, in the sense that queerness is about imagining new relationship structures and making love and family from scratch. Bernie and Leah meet as housemates and then become lovers and artistic collaborators but they also always stay housemates—they share a home together, so the word ends up taking on many meanings.

JF: I so admire your reported work on fatness and fat phobia in literature and healthcare. How is fatness related to queerness in Housemates and what writers are you celebrating and processing with who are writing on these topics now?

ECE: Thank you for that. Leah is fat and nonbinary and there's a lot of thinking in the novel about the ways that being a fat child made Leah "not a girl" in the eyes of her peers and family. I'm also really interested in the book in how queer people often forget to include fatness under our umbrella of liberation; queer people can be just as fatphobic as straight people. Leah—and Bernie too, from a working class perspective—then feels somewhat outside the cool queer scene in their neighborhood of West Philly and this is a tension that propels both characters out of the city and onto the road to search for a different way of seeing and relating to the body.

In terms of writers I'm celebrating who write the fat body with nuance and fullness, I'll never get tired of recommending Martha Moody by Susan Stinson (a historical novel with a hot love affair between two fat women at its core!), Big Girl by Mecca Jamillah Sullivan (for anyone whose mom made them go to Weight Watchers!), though I also cherish the work of Carmen Maria Machado, Sarai Walker, Renee Watson, and others. I believe we are standing at a crossroads where fatphobia in contemporary literary fiction is just beginning to be called out for the hateful rhetoric that it is and writers of diverse body sizes and bodily experiences are feeling newly empowered to render their lives in fiction.

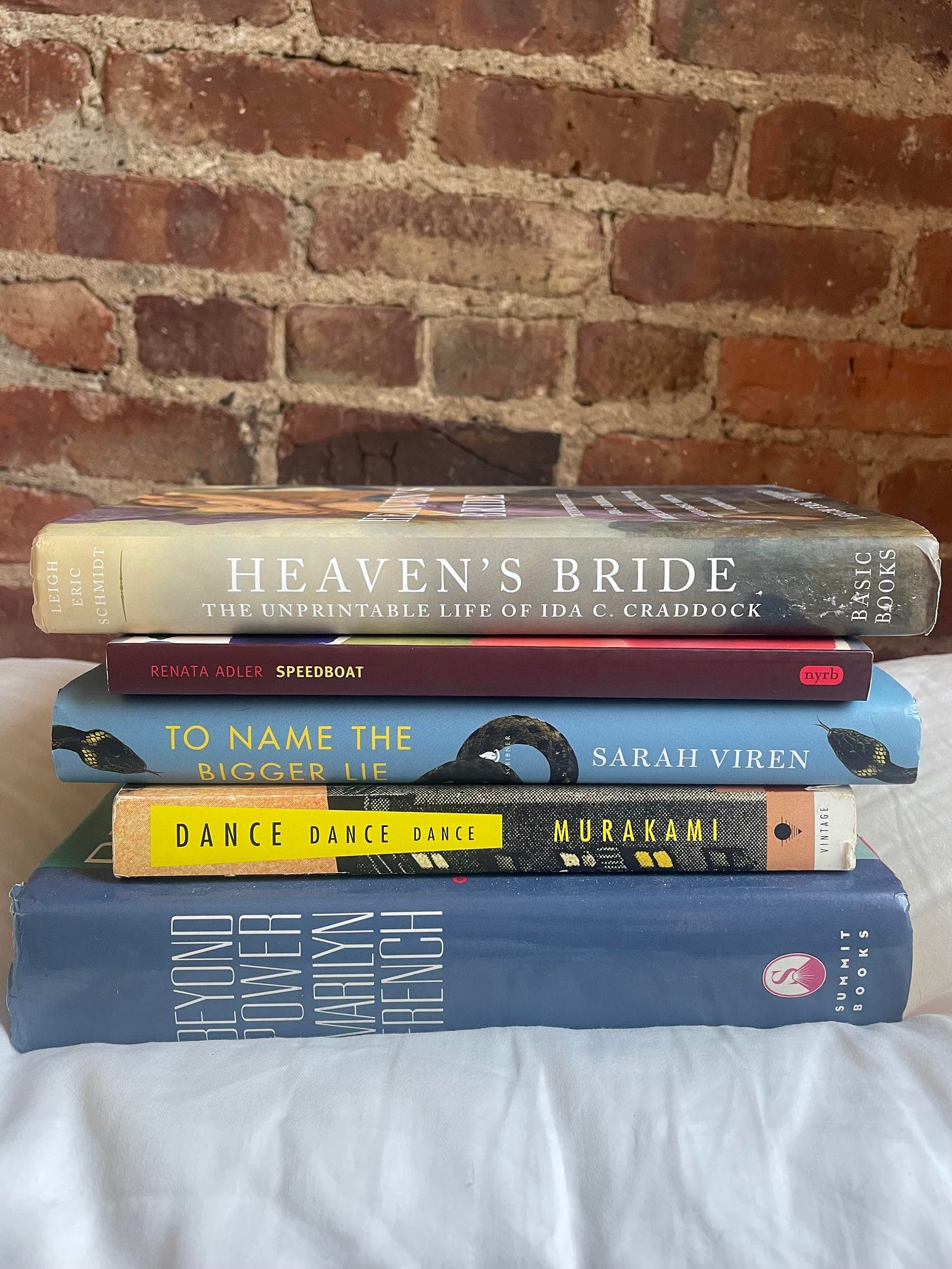

What I’m Not Reading: Sophia Stewart

What I love about this prompt is the sense of shame baked into it. The “TBR pile” looks to the future, surely pronounces that these books are to be read, eventually. But the WINR pile exists firmly in the present: this is what I wish I was reading right now but am not, for various reasons, some more justifiable than others. (You can be the judge.) I feel a twinge of guilt when I spy the below books on my desk, my floor, my shelf. I can only imagine how the books feel, being so long not-read.

To Name the Bigger Lie: A Memoir in Two Stories by Sarah Viren

This book was suggested by my friend Lena, who is a brilliant artist and poet and one of my most trusted book recommenders, as our tastes overlap greatly. Earlier this year she sent me an email with the subject line “have you read this??” and told me how she’d devoured the book over a weekend. It made her think of me, she said, because it just seemed so up my alley; it was her favorite memoir since Chloé Cooper Jones’s Easy Beauty, which I’d raved about and recommended to her. As it happened, I’d already had a copy of To Name the Bigger Lie sitting on my shelf for some time; I’d seen Sarah Viren speak at AWP back in 2022, where she briefly mentioned this work-in-progress, and had been waiting for the book to arrive ever since. So I have every reason to be reading this book. And yet, I am not.

I have had multiple friends and acquaintances tell me I need to read this book because I would like it, including a mustachioed Hinge date who did not really know me but apparently got the gist of my whole thing. I marched into my local bookstore to buy this months ago, so excited to dive into the book, to start braiding my hair like Renata Adler. It has sat on my shelf ever since.

Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals by Marilyn French

I found this doorstopper in a giant crate on the sidewalk near Union Square. I’d just gotten drinks with a writer friend/mentor of mine, and we’d made a pit stop on the way back to the train to buy wrapping paper for a gift he’d gotten his girlfriend. Inside a Paper Source, he told me he had sworn off eating octopus—too smart. As we left, we discovered a trove of books, peppered with old copies of the academic journal Feminist Studies. I picked up this one for the title, of course, and because I’d heard French mentioned by another mentor of mine, as a pioneering feminist writer whose 1977 novel The Women’s Room had been unjustly forgotten. He told me he’d attended French’s funeral with Vivian Gornick, my favorite living writer, and she remarked on how surprised she’d been at the reception of The Women’s Room as a radical, trailblazing text. “We thought everybody knew,” she said. I have yet to open Beyond Power.

Dance Dance Dance by Haruki Murakami

Last year, my friend Juliette and I started a two-person book club. Juliette reads only fiction; I am famously ambivalent about the stuff. For me a novel is a much harder sell than, say, a collection of essays that combine memoir and criticism, or a group biography of women writers who never had children. Juliette and I made our way through two novels in the first months of our club: Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which we hated, and Madame Bovary, which we absolutely loved. For our third, we picked one of Juliette’s very favorite books, Dance Dance Dance. We got a few chapters in—I was intrigued by the narration, which to me evoked a film noir detective’s voiceover—but the demands of work-reading soon impinged on my book club reading and fell behind on our schedule. We put our club on hold.

Heaven’s Bride: The Unprintable Life of Ida C. Craddock, American Mystic, Scholar, Sexologist, Martyr, and Madwoman by Leigh Eric Schmidt

Last summer I read Amy Sohn’s phenomenal book The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age, about the censorious Comstock Act of 1873 (still in effect, btw!) and radical women who fought against it. One of those women was Ida C. Craddock, a visionary sex educator and mystic who married and regularly bedded a ghost named Soph. Obviously, I became obsessed with Ida, and needed to learn more immediately. So I ordered her biography, chomping at the bit. But other, more time-sensitive reading called, so Heaven’s Bride had to wait. And wait.

Sophia Stewart is an editor and writer from Los Angeles, based in Brooklyn. She is the editor of The Millions and a news editor at Publishers Weekly. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The Baffler, and elsewhere.

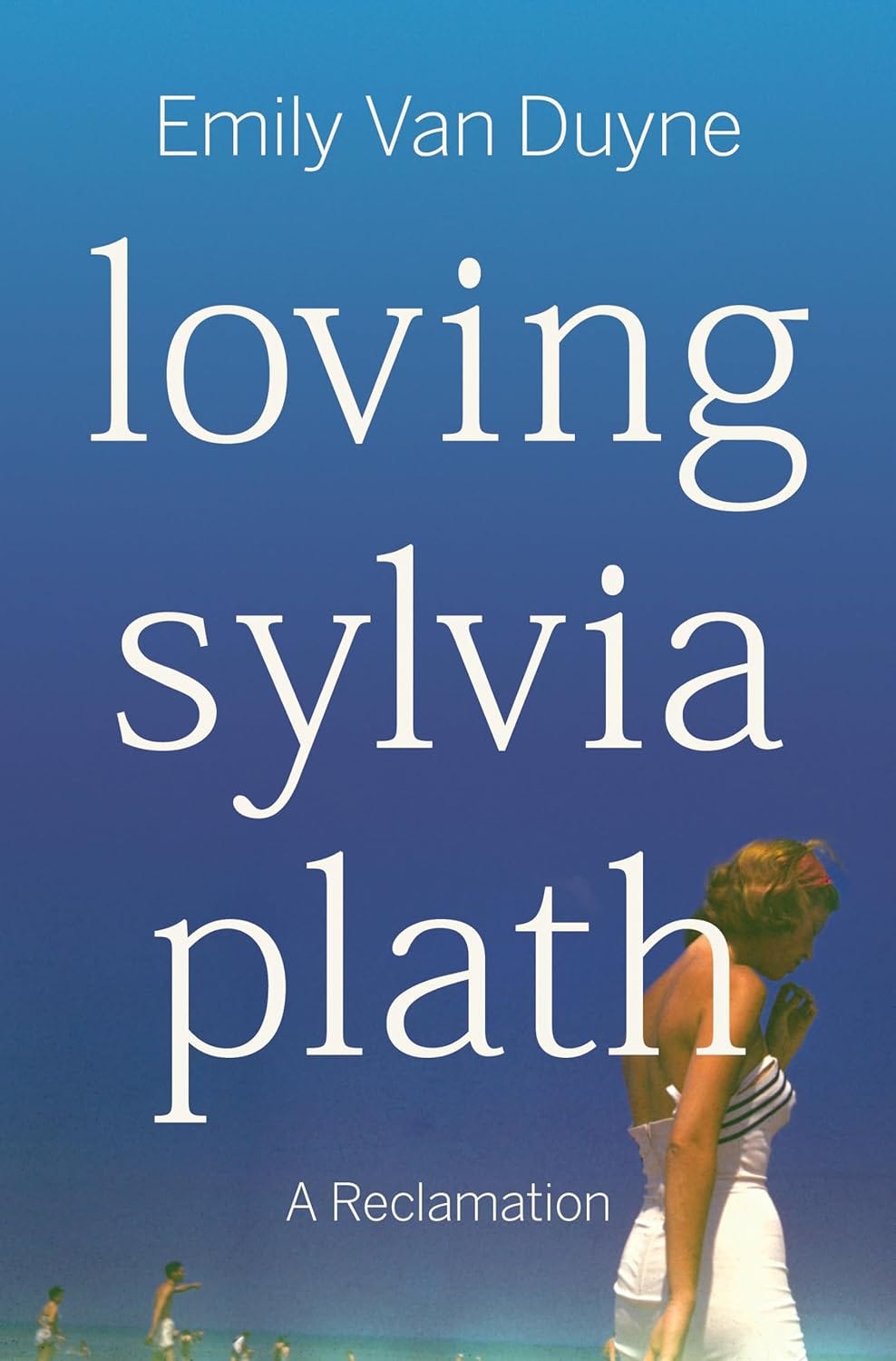

Citizen Sylvia: What Sylvia Plath Can Teach Us about the Threat of J.D. Vance and Pro-Natalism by Emily van Duyne

Some of the discourse surrounding my recently published book Loving Sylvia Plath: A Reclamation has predictably centered on a common trope: Do we really need another Plath book? For decades, this has popped up every time a Plath book is published—you can find similar questions accompanying reviews of Plath books from the 1980s, less than 20 years after her suicide, as though already, we had talked ourselves out on this landmark American writer.

I reject this question outright, as I reject any attempt to cut off intellectual inquiry. But my rejection today is more pointed than ever—in the present era, we need Plath’s work and life story badly. Donald Trump’s recent choice of J.D. Vance as his running mate signals an ever-more terrifying cultural shift toward punitive misogyny as the American norm. Introduced by Kate Manne in her 2017 book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, punitive misogyny is the idea that women who act outside of their prescribed social roles are forced back into them through violence, shame, and social control. In Loving Sylvia Plath, I argue that Plath, ambitious in life and internationally famous for her work after her death, was punished by her husband, Ted Hughes, and prominent male critics for daring to succeed at the level of Hughes. Today, literary critics continue to punish fans and scholars of Plath’s work who laud her radical critiques of patriarchal culture and criticize Hughes for the role he played in suppressing and destroying her work.

Vance’s most recent endorsement of punitive misogyny comes in the form of a 2021 speech he gave that has resurfaced as a result of his vice-presidential run. Speaking to the conservative Intercollegiate Studies Institute, Vance advocated for a new voting system in which “people” with children are given more voting power than those without, as their children would be given a vote cast and controlled by their parents. The more children a couple has, the more political power they wield. I use the word “couple” deliberately, as it’s clear from Vance’s present and prior rhetoric that he understands those worthy of additional voting power to be the hetero parents of nuclear families. Moreover, the ideology that gave birth to this idea—known as “Demeny voting” for the demographer Paul Demeny, who first came up with it in the 1980s—is rooted in an “obsessive focus on fertility rates and immigration,” and widely criticized as racist.

Vance, along with countless members of his constituency, have also virulently attacked the presumed Democratic presidential nominee, Vice-President Kamala Harris, a Black woman, for having never given birth and for being “childless,” claiming this disqualifies her for the office. Putting aside that Harris is, in fact, the longtime stepmother of her husband Doug’s two biological children, the punitive misogyny is clear, here. No prior president of the United States has ever given birth, and several were childless, including George Washington. For Vance and his many supporters, a candidate’s lack of biological children is only viewed as disqualifying when the candidate is a woman; it becomes a more particular thorn when the woman is Black.

Given these facts, and the seemingly unhinged nature of these proposals, it would be easy to ignore Vance as a right-wing radical. But we do so at our own risk. Questioning Harris’s personal choices regarding parenting and proposing a system which gives additional voting power to those with biological children harkens back to the early nineteenth century, when the right to vote depended on race, sex, and the ownership of property. A longstanding, successful argument against universal suffrage had it that white women had no need to vote when one vital purpose of women marrying was to morally influence her husband, who could then carry his wife’s beliefs into the public square. These laws and social norms empowered the white nuclear family, and went far to punish Black families, unmarried Black mothers, and single mothers, more generally since, in many states, it was illegal for Black Americans to marry at all until after the Civil War.

In other words, if you are a white woman with biological children—as I am—and you think Vance and his party aren’t targeting you with these ideas, think again. This is pro-natalism, a movement rooted in eugenics, designed to prioritize the production of white children, keep white women out of the public sphere, and fetishize them in the home. It is further designed to altogether neutralize Black women, and Black families, as a voting bloc.

If you are a white feminist who believes that women like us have historically done what was necessary to liberate all women, I ask you to reconsider our failures in this arena, then and now, so that we might begin the process of correcting them with this election. More specifically, I ask you to reconsider all of this through the particular lens of Sylvia Plath.

When Plath killed herself in February of 1963, she and Hughes were living apart, and she was pursuing a divorce. She left behind a volume of poetry, Ariel, which was primarily a radical critique of marriage and motherhood. She wrote the bulk of Ariel in the fall of 1962, after Ted Hughes left their marriage and their two biological children for a bohemian life in London, where he was conducting multiple affairs. In the wake of Plath’s suicide, Hughes discovered the manuscript for Ariel, as well as the dozen or so poems Plath had written in the last weeks of her life, which she had told many people were vastly different than her Ariel poems, and part of a new book.

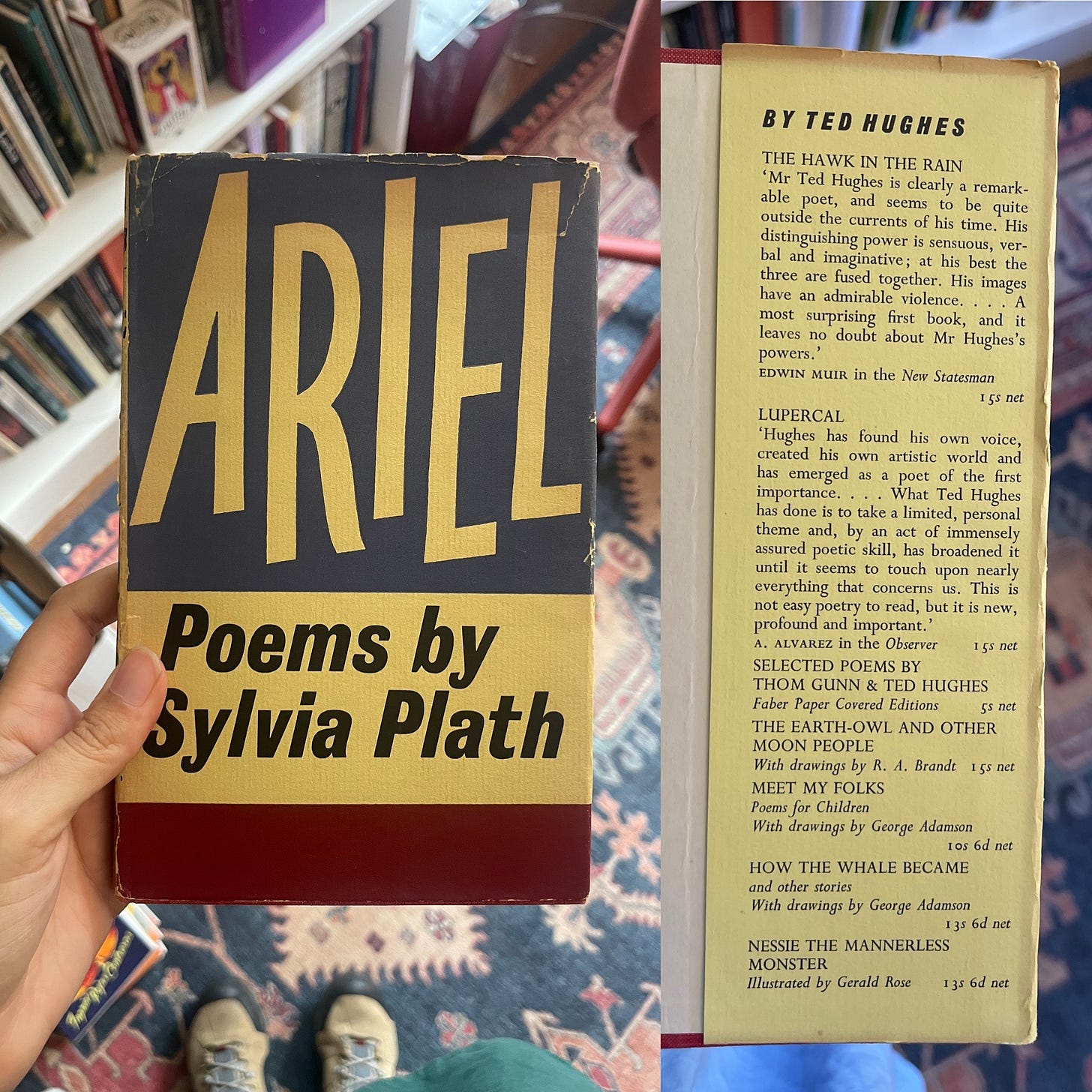

Although Plath had her own British and American publishers, Hughes decided to debut Ariel with his publisher, Faber and Faber. To prepare the manuscript, he removed a dozen of Plath’s poems about marriage and motherhood and replaced them her last poems. While brilliant in their own right, these were largely about death and suicide, written in what her doctor, John Horder, would later term a “psychotic depression.” Ariel was published in 1965, and became a runaway bestseller. The back, inside jacket flap was a series of ads for Hughes’s own books.

This is how we came to know the Sylvia Plath we know today: “Lady Lazarus,” a mad woman obsessed with death and dying, hurtling headlong into suicide via her poetry, and engineered by Ted Hughes. In creating the Plath we came to know, citizenship and its relationship to marriage, was both a vital and veiled question. Because the couple were still married, and because Plath died “intestate” – without a will—Hughes inherited everything she owned, and therefore claimed the right to control editorial and financial decisions about Plath’s writing. He also maintained control of her body. The Hugheses owned a home in southwest England, and Plath had openly expressed a desire to be buried there (in “undulating Devon”). But Hughes shipped Plath’s body to West Yorkshire, his childhood home, and buried Plath in the tiny, hard to reach village of Heptonstall in a grave that would go unmarked for seven years. In those years, Sylvia Plath became an icon of 1960s “extremist” poetry, emblematic of what happens when women artists abandon their domestic duties to try and outpace their husbands—a lonely death and an unmarked grave.

Despite the marked efforts of feminist critics to challenge this narrative, the perception of Plath as a desperate madwoman persists. But it was struck a serious blow in 2017, when letters Plath wrote to her therapist, Ruth Beuscher, emerged, and were read by the public for the first. In stark, impassioned prose, Plath articulates a vision for a woman artist’s life, never sparing how difficult single motherhood makes this. Nonetheless, Plath writes, she can achieve it. She can get a good nanny, write steadily, sell a novel. She is “a feeling and imaginative lay,” and will find another good lover: she does not want to be “an unfucked wife.” It has been well-reported in various Plath biographies that she was also speaking openly about these plans, and her desire for a divorce—a “clean break” from Hughes—at literary and social events in London, including a PEN party—and that the London literati looked askance at her for doing so.

This is unsurprising. In men, the desire for this kind of sexual and artistic freedom at any cost has historically been excused, if not celebrated. Even Diane Middlebrook, an avowed feminist who was once married to the inventor of the birth control pill, wrote in adulatory tones of Ted Hughes’s desire for “predatory” freedom: he wanted to keep a wife (Plath) ensconced in his home and hunt mistresses in the wild (he achieved this when he remarried the 20-year old Carol Orchard, in 1970). Jonathan Bate, in his 2015 biography of Hughes, calls him a jaguar and his marriage to Plath a cage– “Now he was making his bid for freedom. The cage was soul-destroying.” It may have been “soul-destroying” but we should recall that it was also simple to escape—Hughes just had to walk away. Bids for personal freedom in men do not require societal change. Even the relative taboo, in 1962, of leaving one’s wife and children was a small risk for Ted Hughes. The London literary society Hughes and, in a lesser way, Plath, moved in was already, then, heading toward the more relaxed sexual mores that were fully in place by the late 1960s. Even so, while Hughes’s decision to abandon the marriage was taken in stride, Plath’s open anger at her treatment, and frank expression of her desire for a new life, was seen, at minimum, as gauche. At its worst, it was proof she was unstable.

Plath’s fury over the breakdown of her marriage has historically been read as evidence that she was desperate to have Hughes back. But her letters to Beuscher are a lucid bid for sexual, creative, and economic freedom, not a desperate plea to return to a man who weekly visits at the end of her life were “like an apocalyptic Santa Clause.” If they are also fraught, that is no doubt because making that bid as a single mother in 1962 was exactly that. Plath surely felt rage not only at her husband but at a world where, as she wrote in her poem “The Jailer,” to be herself was “not enough.” Hughes had the power to make or break her, socially and professionally.

“The Jailer” did not appear in the version of Ariel that Ted Hughes published in the 1960s, despite Plath’s inclusion of it in her original manuscript, which she left intact on her desk when she died. It first appeared in the magazine Encounter in October 1963. Later, in 1970, it was included in the radical feminist magazine RAT and the anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful. The magazine and the anthology were both edited by the American feminist poet Robin Morgan, who, two years later, published the poem “Arraignment,” which that accused Ted Hughes of raping Sylvia Plath, and killing her body of work and radical politics through a combination of direct censorship and manipulative editing. Morgan’s work ensured that Plath’s poetry and the emerging story of her life would become part of the women’s liberation movement in America.

But which part? Then and now, Hughes’s friends, fans, and scholars of his life and work insisted that Plath was “martyred” by the feminist movement; a 2018 review of her second volume of letters claimed that Plath was “a victim of simplified feminist ideology.” But this so-called simplified feminist ideology was often a deliberate miscasting of feminist readings of Sylvia Plath. “Arraignment” was usually dismissed as a hyperbolic accusation of murder rather than what it is– a satire in the tradition of Dante and Jonathan Swift that accused powerful literary critics of “engaging in a conspiracy to celebrate Plath’s genius while patronising her madness, diluting her rage and suppressing her (alleged) feminist politics.” As Morgan pointed out in the short biography she wrote of Plath at the back of Sisterhood Is Powerful, “There was no movement for women’s liberation at [the time of Plath’s suicide].” Like the Beuscher Letters, Plath’s Ariel poems were written on the cusp of that movement, and embodied its basic principles.

But if Plath embodied the basic principles of feminism’s second wave, she also embodied its predicaments, which would find their critiques in Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work on intersectionality, among other writers. In the United States, second wave feminism was powered by the organizing and labor of Black, brown, and queer women like the members of the Combahee River Collective, but nevertheless wore the popular face of white, straight women like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan– and, in some of its more literary circles, Sylvia Plath. A frequent rallying cry by white feminists in the 1970s, when Plath’s fame was at its height, held that a wife was a slave. The 1973 article “Housework: Slavery or Labor of Love,” by the white feminist writer Betsy Warrior referred to women’s “sexual status” as slavery. Written barely a decade after the passage of the first Civil Rights Act, Warrior ignored the vast difference in socio-economic conditions for white and Black women in America and the ways these grew out of centuries of enslavement. Ignoring these differences was a common oversight then and now, typically presented in the name of “unification.” All women, so this logic went, suffered from sexism, so all women should be grouped into a single category—a tendency Audre Lorde criticized as “white feminism in Blackface.”

In “The Jailer,” Sylvia Plath donned exactly that, writing about a marriage in which a jailer is “...burning me with cigarettes/pretending I am a negress with pink paws.” The poem takes on the difficult subject of marriage to a sadist, someone who delights in cruelty. In 1956, shortly after she met him, Plath told her good friend Jane Anderson that she was worried Hughes was a sadist, a quality he appears to have buried, for the most part, for the duration of their marriage, and which re-emerged in the summer and fall of 1962. Plath wrote to Beuscher then that Hughes “seems to want to kill me.” Certainly, he wanted to kill the so-called marriage of equals Plath believed they shared, to stash her in Devon with their children and live the life he pleased in London. When Plath refused this outright, he appears to have resorted to cruelty and violence in an attempt to force her hand.

It is possible to read this as one version of the fetishization of marriage that politicians like Vance and advocates for so-called “trad wives” want to return to. Plath’s marriage of equals had a great deal to do with citizenry, the ability to enter and participate in the public square, politically, socially, and artistically. She knew that Hughes’s new vision for their marriage was death to this—hence her desire for a life of her own.

It is telling, then, that Plath, an American with strong knowledge of her country’s history of slavery and fraught race relations, chose to recast herself as a Black woman in a poem about the conundrum of marital cruelty. The speaker embodies the historical certainty that, as a white woman, she cannot be cast aside as easily as the jailer would like. He must, therefore, transform her into the kind of woman he can do these things to with impunity—a “negress” who Plath commits a further crime against when she animalizes her as having “pink paws.” The jailer’s specific cruelty, here, is also deliberately racialized. He burns her with cigarettes, a reference to the branding of enslaved women in antebellum America.

The critical canon has spent decades wringing its hands about Plath’s anti-Semitic language, her appropriation of Jewish identity and the particular tragedy of the Holocaust. But it has remained relatively silent about her similar use of anti-Black slurs and stereotypes in her work. Plath’s famous claim that she “may be a bit of a Jew” was, as the critic George Steiner wrote, “a subtle larceny,” but transforming herself into “a negress with pink paws” has been recently excused as one of the ways Plath articulated women’s fight for freedom from patriarchy. This last is a not-so-subtle larceny. If identity is a property that can be stolen, as Steiner’s famous quote suggests, then calling Plath’s act of literary Blackface a freedom fight is a double theft, snatching both Blackness and its role in Black women’s fight for liberation from racism and sexism, and handing them to a white woman on a proverbial silver platter.

The actual use of branding in slavery is memorably depicted by Toni Morrison in Beloved, when Sethe recalls for her daughters one of her few memories of her mother:

“Right on her rib was a circle and a cross burnt right in the skin. She said, ‘This is your ma’am. This,’ and she pointed. ‘I am the only one got this mark now. The rest dead. If something happens to me and you can’t tell me by my face, you can know me by this mark.’ Scared me so. All I could think was how important this was and how I needed to have something important to say back, but I couldn’t think of anything so I just said what I thought. ‘Yes, Ma’am,’ I said. ‘But how will you know me? How will you know me? Mark me, too,’ I said. ‘Mark the mark on me too.’”

“Did she?” Sethe’s daughter, Denver, asks, and Sethe, chuckling, reports that her mother slapped her in response. Far from simple evidence of victimhood or a sadistic power play, this branding marks Sethe’s mother as literal property. She employs it to give her daughter a way to identify her in an act equal parts cleverness and desperation. This branding of slaves and cattle gave rise to the use of the word brand in marketing; in her posthumous fame, Plath became the ultimate literary brand, the Sad Girl, a commodified identity sold to young women as a personality they could try on and then discard, just as Plath can erase her Blackface and jettison her role as a sexual prisoner, or slave. That Plath’s brand was closely associated with images of historical horror, most famously the Holocaust, was immediately recognized as troubling, and objected to by the literati. But analogous images of anti-Black racism, including branding and scarring, barely warranted discussion, because the anti-Black racism they portray is also at the root of the culture that raised and received Sylvia Plath—the one presently attempting to disqualify a Black woman presidential candidate for a lack of biological children. The bodies that served as the etymology for the commodified Plath could not be un-branded: “What happened to her?” Denver asks Sethe, about her mother.

“Hung. By the time they cut her down nobody could tell whether she had a circle and a cross or not, least of all me and I did look.”

***

Beloved is most famous for its central act, when Sethe commits infanticide rather than return her children to slavery. But there are other, less-remembered instances of infanticide in the novel. Sethe has a flashback to being told that her mother killed her newborns who were the result of sexual assault by white men. Sethe, the result of a union with another enslaved man, she kept, and gave her father’s name. Beloved is, in one sense, a de-mythologized retelling of Medea, but it upends Euripides’ notion of filicide and infanticide as either rare or monstrous since, as Morrison wrote in her Foreword to the 2004 Vintage International edition of her book, “Assertions of parenthood under conditions peculiar to the logic of institutional enslavement were criminal.” To assert her parenthood, Sethe would, ideally, protect her children from her former owners; her choice to kill, rather than return them to the slaveholders who raped her and drove her husband mad, is proof she has none.

Beloved and Medea are in grim conversation with Plath’s poem “Edge,” written six days before her suicide. In it, a cool, third-person speaker runs rapid-fire through a series of images that begin with a dead woman from classical antiquity. She is “perfected,” with one dead child at each breast. The poem ends with the moon, cruel, magisterial, and distant, who is, “She is used to this sort of thing./Her blacks crackle and drag.” As a single mother, Plath’s desire for liberation was grounded in and complicated by her children, Frieda and Nicholas, who were not-quite-three and just-turned-one at the time of her death, and in the house when she killed herself. “Edge” has been widely interpreted to mean Plath intended to kill them when she died by suicide. In Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath (2020), Heather Clark reported that both Olwyn and Ted Hughes, the only people to read Plath’s last journals before Ted Hughes destroyed them, said she wrote there about exactly this. Clark offers further proof that filicide was on Plath’s mind in the last weeks of her life: in earlier drafts of “Edge,” she included, then crossed out, the line, “She is taking them with her.”

Plath did not kill her children, but “Edge” forces us to consider the ways she has come to symbolize both the oppressed white woman (for white feminists) and, for intersectional feminism, the white woman oppressor granted privileges and freedoms she hardly knows she has as the result of her race. The description of filicide in Plath’s work, and the possibility of it in her biography, are exoticized and romanticized, treated as proof of her monstrousness and her power, or as an example, for white feminists, of how Plath’s position as a single, abused mother lent itself to her suicide and consideration of filicide. Sethe’s actions can only be criminalized– were she to flee rather than kill her children, she would face the same consequences, imprisonment, re-enslavement, corporal punishment, or hanging.

We can learn little from a bald comparison of the experiences of free white women with enslaved Black women, since in many ways the experiences are incomparable. Instead, we should read “Edge” through Toni Morrison’s Beloved. This idea, borrowed from the scholar Malin Walter Pereira, “broadens the discourse to include an African American perspective on female selfhood and truth.” For Pereira, who re-envisions Plath’s famous bee poems through Morrison’s “parable of the soldier ant queen in Tar Baby,” reading Plath through Morrison “reveals limitations in the white female vision of a self,” with its investment in romantic love as the ultimate endgame. However we as white feminists read Plath’s decision to end her life, or consider the simultaneous murder of her children, we read them as choices relative to her marriage—consider, for example, Clark’s description of “Edge” as a “poison arrow” for Hughes.

Faced with her stark lack of choice, Sethe finds agency in the life she carves for herself in slavery’s aftermath. The best white feminism can do for Plath is explain away her death, rather than envision new ways to live. We should bear these limitations in mind as we approach another election season, in which racist, misogynistic attacks on a Black woman candidate will be brutal, unrelenting, and aimed to convince white women to abandon any vision of collective liberation.

***

When Ted Hughes published Ariel in the mid-1960s, he ordered “Edge” as the penultimate poem, lending credence to the idea that Plath wrote it as a suicide note. Robert Lowell wrote a Foreword to the American edition of Ariel; his dominant mode of reading it was suicidal, but he also gave us Plath the murderer, comparing her to Medea: a “super-real, hypnotic, great classical [heroine].” It’s hardly the job of a poet writing a Foreword to a book of poetry to explore the socio-economics of single motherhood, suicide, and filicide. Still, the image of a Medean Plath drove home the dangerously reduced idea of a woman– or rather, women– doing the unthinkable for no other reason than the satisfaction of rage, or revenge, at a lover gone astray: “Hell hath no fury, etc.” Medea is best remembered as Euripides’ anti-heroine, a woman who murdered her sons when her husband was unfaithful to her. In the 1960’s, this fit neatly, if erroneously, with the mix of rumor and ugly facts hounding the end of the Hugheses’ marriage and the end of Sylvia Plath’s life.

But Lowell’s likening Plath to Medea was apt in ways unconsidered in his Foreword, which shed light on her life and legacy, and remind us that it is not only Plath’s story that needs reclaiming, but so many of the mythologies through which we read her, which continue to inform our understanding of womanhood, today. The backstory of Medea’s life and marriage involves, like Sylvia Plath’s, sacrifice, exile, and extreme acts in a desperate state– an emotional state and a hostile country. Medea is a foreigner (in some translations, she is referred to as a barbarian) living abroad, who left her home and family behind to marry Jason, a dethroned Greek king, trying to regain power (with her help). Since Medea wasn’t Greek, Jason could dissolve the marriage with ease and force her, and his own children by her, into exile.

Although reduced to the act of filicide, Medea was also a powerful witch and the daughter of a king. She met her husband, Jason, when he attempted to capture the Golden Fleece from her father, Aeetes, the King of Colchis, or modern-day Georgia. Jason needed the Fleece to establish his authority as the rightful king of Iolcus. King Aeetes, angered by a foreigner trying to take what was his, told Jason he could have the Fleece if he completed a series of impossible tasks. Hopeless to accomplish what was before him, Jason went to his ship to consult with his men, the Argonauts; there, the King’s nephew told him Medea could help. Medea, with a push from the gods Hera and Aphrodite, had already fallen in love with Jason when she saw him dining with her father, earlier. She agreed to help in exchange for the promise of marriage. With Medea’s guidance, Jason captured the fleece and became king. Without her, he would have been nothing.

Which is possibly close to what Ted Hughes would have been without Sylvia Plath. When the couple met in 1956 at Cambridge University, Hughes was working odd jobs and writing poetry he sometimes published in university magazines, mostly under pseudonyms. He chose to publish a handful of poems under his own name when he and some writer friends put out a small literary magazine called St. Botolph’s Review, named for the church in whose converted rectory– and chicken coop–where some of them boarded. Plath, studying English Literature at Newnham College in the first of a two-year Fulbright Scholarship, read it and was impressed enough to wrangle an invitation to the launch party. There, she met Hughes for the first time. They were both drunk. She recited his poems to him, shouting over the loud jazz music. He kissed her, and stole her headband and earrings. In return, she bit him on the face.

That was in February. By June, they were married. Although they agreed to devote their time and energy to writing, Plath took on the additional job of promoting Hughes’s poetry; she believed he was a genius. In a 1956 letter to her one-time boyfriend Peter Davison, already an editor at the Atlantic, she wrote that she had discovered Hughes and was acting as his agent (by the end of the letter, she fesses up to having also married him). She typed and ordered Hughes’s poems into a manuscript, targeting contests she knew he could win. They hadn’t been married a year when this paid off. His book The Hawk In The Rain won a poetry contest sponsored by the Poetry Center of New York City’s 92nd Street Y, judged by Marianne Moore, Stephen Spender, and W.H. Auden. Plath knew two of the three judges personally. For the whole of their marriage, Plath played the dual role of secretary and agent for her husband, typing and submitting his work, negotiating his contracts, and managing his finances. Like Medea, she had an insider’s knowledge that she used to protect and promote her husband– in Plath’s case, of the American literary and publishing scene, which she used to make Ted Hughes famous.

Like Medea’s filicide, Plath’s suicide became her stand-out act, a distraction from the larger scope of her life story. Like Plath, Medea married a powerful man from another land, leaving behind her life and home; like Plath, she was the instrument through which that man gained power at home and abroad. Medea was warned by her family not to go with Jason since, if she left behind her homeland, they were powerless to protect her. Even a royal woman’s identity was bound first to her father, then her husband. When that husband left her for the daughter of Creon, a more powerful king, Creon banished Medea and her sons and she became a stateless person, a refugee, along with her sons– in the ancient world, a fate worse than death. So, she killed them. Far from a simple act of vengeance, this was the same logic Socrates applied to his choice to drink hemlock rather than flee his prison, when his friend Crito offered to break him out. If Socrates escaped, his wife and children would have been hunted, and lost their Athenian citizenship. If he died honorably, they were safe. Even as a convicted criminal, his children were granted protections Medea’s sons lacked, as the children of the king’s cast-off wife.

Plath was hardly stateless at the time of her death, but she was living in a foreign country, far from most of her friends and all of her family. Hughes was working in tandem with Al Alvarez, another prominent critic who Plath had briefly dated that fall, to keep her from the kind of social and literary connections which kept her float emotionally and financially. By the end of January 1963, Plath’s checking account balance was £59. She was aware, too, that Hughes had functionally abandoned her children, and had an expressed lack of affection for their younger child, Nicholas, who Hughes called “the usurper.” In 1962, he wrote to his sister Olwyn that he was planning to leave the children forever—Frieda, their older child, would be “a problem” because he had spent more time with her. But he and Nicholas hardly knew one another, so what did it matter? Later, in a particularly Medean twist, Hughes would force his son to give up his American citizenship, and abandon the country of his mother.

In the last weeks of her life, Sylvia wrote “Kindness,” with the unforgettable lines, “The blood jet is poetry/There is no stopping it./You hand me two children, two roses,” an inescapable nod to Hughes’s radio play, Difficulties of a Bridegroom, in which his protagonist gives his mistress two roses. Inescapability was precisely what Plath was writing about in “Kindness,” a poem as much in conversation with her poem “The Rabbit Catcher” as it is with Difficulties of a Bridegroom. Rabbits, dead or dying, appear in both poems, as do mugs of tea. In “The Rabbit Catcher,” the speaker envisions “hands round a tea mug, dull, blunt/Ringing the white china,” an intentional nod to rabbits having their necks crushed in the snares the speaker sees (“Snares” was one of Plath’s original titles for the poem).

By the time she wrote “Kindness,” the mugs of tea no longer stand-in for death or strangulation, and are instead a futile act of sweetness in the face of disaster. The speaker, ensnared in an impossible domesticity, is saddled with two children and two roses, the stand-in for her husband’s infidelity; an American in need of money, love, and general help, she is given a very English cup of tea, “wreathed in steam:” “Sugar can cure everything, so Kindness says…/Its crystals” are “a little poultice.” But sugar cures nothing; that is the point.

“Kindness” was a poem I came to later in my life. Before I understood much about it, I read it dozens, maybe hundreds of times, lingering over the “blood-jet,” beguiled by Plath’s risk and daring, trained to see her as a nihilist, the self-same poet who believed, per Robert Lowell, that life and poetry were “simply not worth it.” This was the Sylvia Plath of Joyce Carol Oates who, decades before her terrible takes on Twitter, wrote that Plath did not believe other human beings were “real”—unless, of course, they were capable of hurting her. Oates extended this argument to Plath’s own children, who she believed were not real to Plath, were there only “for her image-making mind.”

As a creative young woman obsessed with Plath’s life and death, I could recite “Daddy” by heart, and thrilled to the juxtaposition of nursery rhymes with vampires, Nazis, and Plath’s audacious rage, which I thought was the key to understanding her story and my own. My telephone was off the hook to the fullness of Plath’s predicament, the roles politics and power played in it, and the ways both had frequently been deliberately covered up by those in charge of her legacy. “What is so real as the cry of a child?” Plath writes in “Kindness,” calling out to Hughes– If you can’t hear me, can you hear them? For a long time, I was deaf to that cry. I did not discover the fullness of “Kindness” until my thirties, when I was a single mother asking her son’s absent father, Why can’t you hear him? I was doing whatever I could to regain control of my life. I was learning an embodied lesson about gender and power, one I would never forget. My ex was a poet, too, free to come and go as he pleased, write what he wanted, tell or not tell the world about his son, who he abandoned, at will—what did it matter, to him?

But my life was governed by my child, who was now seen as less than because he was fatherless. As I, too, was seen as less than, for being without a husband, for being a single mother. My ability to participate in the public square had changed, in ways I found shocking.

I should not have found them shocking. I grew up white and woman in America. My worth has always been tied, economically, to my ability to marry the right man, have the right children (things I steadfastly refused to do). If I grew up loving Plath and deprived of the knowledge of how much this problem informed her life, and her work, I should also not find this shocking—it’s by design. Plath’s frank accounts of the ways her public life was curtailed by her refusal to participate in a marriage that constrained and coerced her were deliberately suppressed for decades. But we have them, now. As her readers, we can use them to fuse art and politics in our present moment, to take Plath’s status as a white feminist icon, see it for what it truly is, and vote like our lives as full citizens of this country depend on it. Because they do.

Emily Van Duyne's book Loving Sylvia Plath: A Reclamation is out with W.W. Norton & Co. An associate professor of writing at Stockton University, she is the recipient of fellowships from the Fulbright and Mid Atlantic Arts Foundations, and from Emory University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and children, and is at work on a book about the history of campus sexual assault in the United States.