Study for Obedience: The Womb House Books Review

A conversation with Sarah Bernstein, author of Study for Obedience, Ruth Franklin on the genius of Shirley Jackson, and what PR consultant Lauren Cerand isn't reading.

It’s been a busy spooky season here at Womb House Books! We held our monthly bookclub on the genius of Shirley Jackson, and called forth the spirit of Sylvia Plath with a séance on her birthday. For our November book club pick, we have chosen Kristen R. Ghodsee’s eye-opening Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism. From now on, the book club will be meeting twice in shop and at least once online. In November we have author events celebrating Kate Hamilton’s Mad Wife and Sarah Thornton’s Tits Up.

Our fifth issue contains a discussion on Shirley Jackson with her biographer Ruth Franklin, a conversation with the brilliant novelist Sarah Bernstein author of Study for Obedience, and “What I’m Not Reading” by public relations consultant and voracious book person Lauren Cerand.

Subscribe for more announcements and visit our website for more events.

Ruth Franklin on the Lasting Legacy and Genius of Shirley Jackson

In preparation for our October book club on the genius of Shirley Jackson, I reached out to Ruth Franklin, author of Jackson’s biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, to ask why Jackson’s work still resonates, more than 75 years later. —Jessica Ferri

The feminist critic Elaine Showalter said on a podcast in 2009 that Jackson was the most important mid-20th century writer whose work had yet to be reevaluated in terms of its value. Do you think this is still true, or has Jackson gotten her due?

As far as I’m concerned, there can never be enough discussion of Shirley Jackson! But when Elaine Showalter made that statement, much of Jackson’s work had either fallen out of print or (in the case of the short stories and letters) had yet to be published. Since then, nearly all of it has been brought back into print—including two volumes published by the Library of America—and there’s been a groundswell of criticism looking at her writing in all dimensions, from many different perspectives. The foundation has been laid for a new generation of Shirley Jackson scholars to take it from here.

Why do you think Jackson’s work has stood the test of time? What still resonates for readers, 75 years on?

Jackson diagnosed the elements of horror in daily life: the racism of wealthy suburban white people, the predatory behavior of powerful men, the ways in which society can turn on its most vulnerable members. Does any of that still sound familiar?

What did you think of the LOOSELY inspired by Netflix series The Haunting of Hill House?

I was mostly entertained and intrigued by it, and I thought it stayed true to Jackson’s vision of what Hill House was—up until the last two minutes. I recapped it for Vulture, where you can read my thoughts on each episode at great length!

If a person has read the short fiction, The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, where would you recommend they start with her lesser known novels? And what is your personal favorite of Jackson’s novels?

My personal favorite is The Haunting of Hill House—so much so that I actually have a tattoo inspired by it. But all of the lesser-known novels are interesting in different ways. My favorite of her early work is The Bird’s Nest, a fascinating account of a woman suffering from multiple personality disorder that was part of the boom in interest in that diagnosis during the mid-1950s. Jackson’s book isn’t as well known as The Three Faces of Eve or Sybil, probably because it’s darker and more complex.

Don’t overlook her memoirs—Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. Both are very funny (if also subtly bitter) accounts of her family life.

Are there any contemporary writers publishing now that you feel are Jackson’s progeny?

Writers from all over the creative spectrum have told me that Jackson inspires them in many different ways, but a few who feel directly in conversation with her are Kelly Link, Carmen Maria Machado, and Kristin Roupenian.

What can Shirley Jackson’s work tell us about being a woman in the world, and what lessons still resonate with women today?

Jackson depicts being a woman in the world as a pretty fraught business. We’re never more than a stone’s throw from disaster. But our creativity is a potentially bottomless source of power.

Ruth Franklin’s next book, The Many Lives of Anne Frank, will be published in January 2025 by the Yale Jewish Lives series. Her book Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (2016) won numerous awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, and was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2016, a Time magazine top nonfiction book of 2016, and a “best book of 2016” by The Boston Globe, the San Francisco Chronicle, NPR, and others. She is also the author of A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction (2011), which was a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Writing. Her criticism and essays appear in many publications, including the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, the New York Review of Books, and Harper’s. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in biography, a Cullman Fellowship at the New York Public Library, a Leon Levy Fellowship in biography, and the Roger Shattuck Prize for Criticism. She teaches nonfiction writing in the MFA program at the Columbia University School of the Arts and writes a newsletter about biography and criticism at ruthfranklin.substack.com.

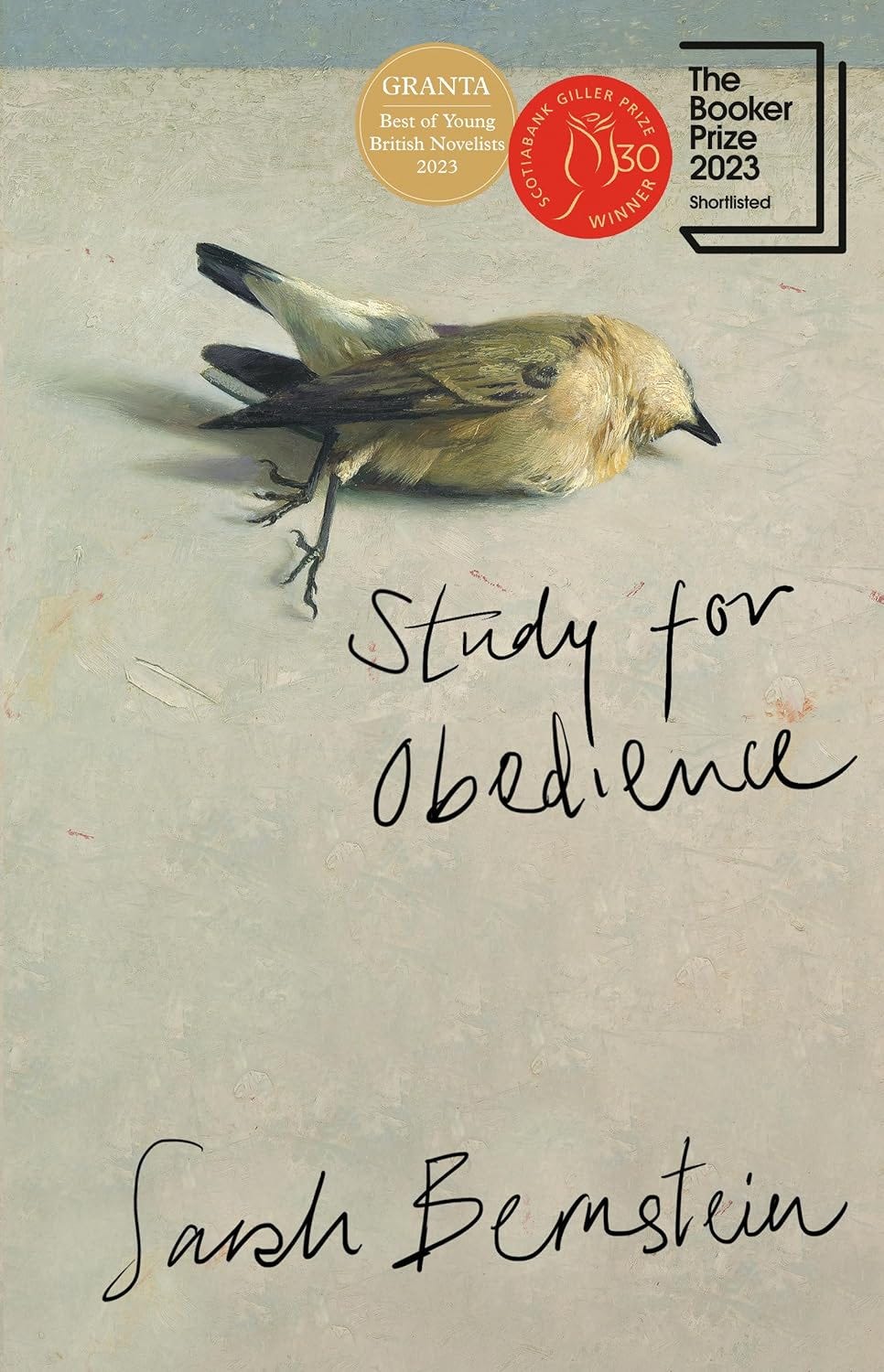

How Innocence Can Be Weaponized: A Conversation with Sarah Bernstein, author of Study for Obedience

Once in a blue moon I enjoy a book so intensely that I actually fear to speak with its author, anxious to break the spell of the work. But I’m glad that Sarah Bernstein took the time to speak with the WHB Review about her second novel, Study for Obedience. Absolutely chilling and eerily prescient, Study for Obedience is not only a recent favorite, it has become one of my favorite novels. I spoke with Sarah via e-mail correspondence from her home in Scotland. —Jessica Ferri

I have to admit I picked up Study for Obedience because I read someone somewhere compare your writing to that of Thomas Bernhard, who is my favorite novelist. How do you feel about that comparison?

I am also a big fan of Bernhard. I read most of his novels in my last year of university, usually during my shifts at a clothing store that no one ever came into. He was having a moment in the late-00s in Montreal, I think because the Penguin translations were coming out, and those books really changed how I thought about writing at the level of the sentence—the possibilities for arranging sentences, for their internal rhythm, their rhythm within a paragraph.

I do think there is a commonality there, not only in style, but also in the stain of history. Bernhard was particularly focused on Austria's collaboration with the Nazis. Do you consider Study for Obedience to be a historical book? What drew you to the idea of an outsider coming into an unfriendly (that's putting it nicely) place?

I consider it to be a book about the transmission of history. I was thinking about what it means to grow up in an environment where the experience of history that is handed down, from childhood on, is one of ongoing catastrophe, where each new catastrophe sits in the last and foregrounds the next. What kinds of people might that shape, capable of what actions? How might it impact the way people see themselves in relation to the world, the way they conceive of their own agency? I was interested in exploring the work of 'innocence': who is afforded a position of innocence and on what terms. On the one hand, I wanted to understand how innocence—seen as a stable, permanent category of existence that is granted by having been badly treated ourselves—can be weaponised. On the other hand, I wanted to think about why we tend to withhold sympathy for other people until those other people have proven their 'innocence', holding them to a standard we ourselves could never live up to, but which nevertheless becomes a condition for admitting the humanity of the other.

Is innocence defined as "having been badly treated ourselves"? I think of it as having committed no crimes. How can innocence be weaponized? I think of it more as complicity . . . that someone or something (like a state) can be innocent of crimes but guilty of complicity or lack of action.

There is a kind of circular logic here which the book in part tries to work out. If we have this idea (and I think this is unfortunately more prevalent than most of us would like to admit) that, in order to see and to acknowledge the pain of others, we need to see them as 'innocent' (as having committed no bad deeds, no crimes, having moreover no bad intentions or thoughts) then what follows in this logic is that if someone has been victimised, they themselves must be innocent. Where innocence is weaponised, this state of innocence comes to inhabit a perpetual present tense, in which the experience of a traumatic past ensures an enduring innocence and renders one incapable of wrongdoing. There is a problem of agency here and of admitting agency.

I have been preoccupied by these problems for a long time, as a Jewish person witnessing Israel's crimes against Palestinians. It isn't just that these crimes are being justified, it is also that they are being denied via the various applications of the logics described above, and via the monumentalisation of the Holocaust. Naomi Klein writes about this, about how some kinds of Holocaust education in Jewish schools, like the one she went to and like the one I went to, effect a re-traumatization, rather than a remembering: 'Remembering puts the shattered pieces of our selves back together again (re-member-ing); it is a quest for wholeness.... [R]e-traumatization is about freezing us in a shattered state; it's a regime of ritualistic reenactments designed to keep the losses as fresh and painful as possible.' She argues that this kind of education keeps us in a state of outrage and indignation, rather than 'ask[ing] us to probe the parts of ourselves that might be capable of inflicting great harm on others, and to resist them.' We have seen what can follow from this kind of orientation to the world.

In the book, the sister and the brother have adapted quite differently to their shared upbringing, but for both of them history is ongoing. Some people thought the book did not take history seriously enough because it treated it as a 'vibe'. I find this interesting, because of course history is a vibe, in the sense that it is lived and felt in the body. It's the weather we live in, it shapes our lives, our relations with others, it allows us certain possibilities while foreclosing others. To acknowledge this is precisely to take it seriously. Only someone who doesn't feel the weight of history in their own life could insist upon an objective approach.

How would one 'take history more seriously' as a novelist? Do these people want more grounded, historical details?

It seems that way, but it is possible I am misinterpreting this. I think short form literary criticism doesn't lend itself particularly well to nuance, which means that critics tend to focus on a single reading of a novel that might be more open ended, or not necessarily interested in resolution. In order for a reading like this to work, the story either needs to be understood as literally true—reflective of an objective historical reality—or as a straightforward allegory, where the story is just a stand-in for something else.

As for what drew me to the idea of an outsider to an unfriendly place: it's an interesting question. I've sometimes answered this by saying that, when I started writing the book, I had moved to a small and remote village in Scotland, where the people are very friendly, but I wondered what it would be like if they and I had been completely illegible to one another. In fact, I think I struggled to articulate my interest in this dynamic for a long time. Because, although the narrator is an outsider in the sense that she wasn't born in the place, it is the place her family comes from, where they were exiled from. I guess I had been thinking about the impossible dream of return (I am borrowing from Saidiya Hartmann's Lose Your Mother in using that phrase). What is this character, what is her brother, looking for in going back to this place? What they find certainly isn't home anymore, so how does a place that once was a home become not a home? By what process of estrangement?

I felt more than a process of estrangement, though, particularly for the sister, I felt pure violence and malevolence from the townspeople. Can you say more about this?

The violence is present both concretely, in the violent history that led to the exile of the narrator's family, and in a slightly more ephemeral or abstract way in the present—through the suppression of this history, and the lingering suspicion of her that is tied to the longstanding and multifarious suspicion of Jews in Christian societies.

The narrator of Study for Obedience seems to only experience peace and joy when she is alone. At one point, she describes looking out the window as being seen as "selfish and inconsiderate." How is obedience a particular expectation for women?

In the sense that obedience is a characteristic associated with passivity, it is often feminised. It’s also associated with the generational order—children obeying their parents—and the shaping of subjects as members of particular communities—people obeying explicit and tacit laws and rules for living. All of these converge for the narrator, as they do for many people, only she takes on the project of obedience with a kind of zealousness or savage pleasure. I became interested in the idea of obedience as it relates to performances of femininity when I went to a retrospective of Paula Rego’s work a few years ago, and where I found the quotation that became one of the novel’s epigraphs: Women can be obedient and murderous at the same time. How could a passive trait like obedience take on a kind of agency, becoming even murderous? It didn’t seem possible, and yet in Rego’s domestic tableaus we can see this dynamic come alive. That was one of the novel’s starting points.

Is that obedience a kind of revenge?

I suppose the answer to this depends on how much agency you attribute to the narrator, and how much you believe in a kind of magical thinking. Personally, I am very interested in, if not quite revenge, at least the holding of grudges.

I wonder how you came to writing. When did you start writing fiction? How long did it take you to write your first novel, The Coming Bad Days, and then, Study for Obedience?

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t writing stories. From childhood, telling or writing stories (often just to myself) has been the way I have made sense of the world around me, and how I’ve found modes of expression for thoughts and feelings I could not otherwise find an outlet for. I have always been a shy person, and I am not particularly good at speaking or responding in the moment, my brain just doesn’t work that way. I am a slow thinker. I’ve always gone away to work things out through writing, at which point I am better able to speak the things I think.

The Coming Bad Days took me about two years to write. It was a very unhappy time for various reasons, but I told myself: if I could just keep writing, I could keep going, so that’s what I did. I sat at my desk every night and wrote and little by little the book got bigger. When I finished it, I had done something, even if no one ever read it and it never got published, I had done it once, which meant I might be able to do it again. It was very important for me because of that.

I had been writing sections that became part of Study for Obedience for a couple of years before I realised they appeared to be coming from the same voice. Once I knew this, I took some time away from writing to read other things and think about the shape of the story so that when I came back to writing after teaching was over for the year, I finished a first draft of the book in probably three months.

When setting out with a novel, what guides you? Plot? Character? Neither?

Voice! I get a line in my head, like hearing a musical phrase, and I write it down, and I follow the sound of that line to the next, and the next.

Why is the novel the form for you?

I like the novel's capacity to hold opposing truths, to say yes and no at the same time, to pose questions rather than to answer them. I think there is also something about duration here, too, since in my novels I have been interested in how history resonates in the present in various ways.

Sarah Bernstein is from Montreal, Canada, and lives in Scotland. Her writing has appeared in Granta among other publications. Her first novel, The Coming Bad Days, was published in 2021. In 2023 she was named as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists.

What I’m Not Reading by Lauren Cerand, public relations consultant

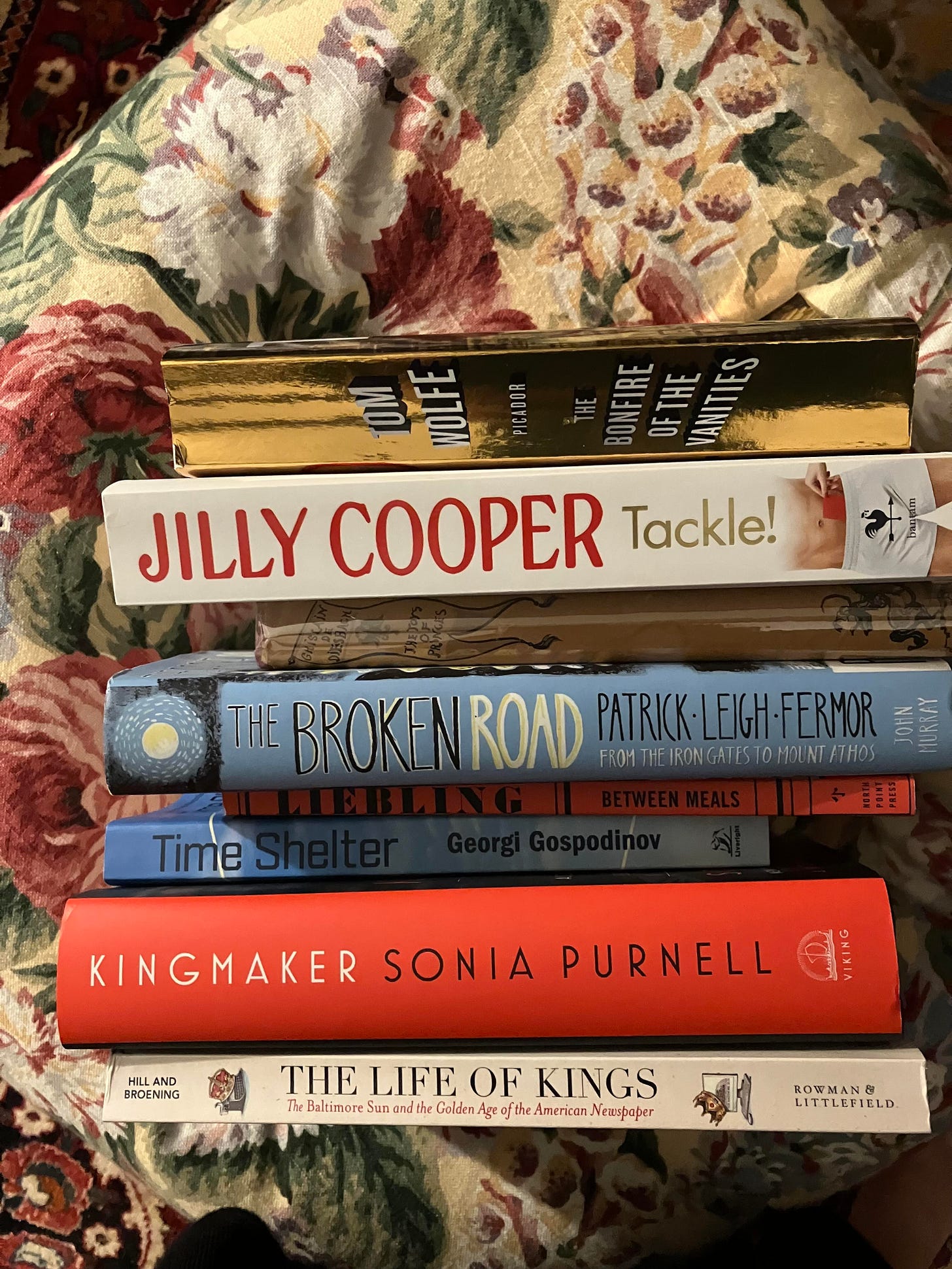

There are a few sureties in my house: you will hear my favorite radio station, TSF Jazz, playing, smell some scent of tonka or amber in the air, settle in among plenty of ottomans and alpaca throws, and you will be offered a drink, and yes, surrounded by books. Herewith, my list of “What I’m Not Reading” or what I think of as books for the bath or in front of a tended fireplace, two key things I don’t have (yet):

Bonfire of the Vanities: my paternal grandparents were flappers of some renown, so there is a real sense in my family that to say that New York is “over” is a bit pathetic: perhaps for you, dear. Still, as a (former now) New Yorker for more than two decades, I hold the quintessentially romantic view that the best New York was the one that ended moments before I arrived. This is especially true in matters of literature.

Tackle: When I first moved to Baltimore, I listened to Jilly Cooper novels while driving around and they would be more formative for my social life than I realized. My friend, the Scottish writer Sheena Cook, brought me this one from the UK and I have to read it either before or after I watch the television adaptation of Rivals, there being no real substitute for the rampant satisfactions of the Jilly-verse.

The best thing about having fantastic relationships by post with several used book dealers is I will get something like The Toys of Princes with an inscription from Bill at High Valley Books that says, I hope you don’t have this yet. Does anyone?

One Christmas break when I didn’t have the money to join friends in Tulum, one of the gods of publishing showed mercy on me and we went to the house of a grand dame who asked me to get a bottle of champagne from the kitchen and I said, how will I know where it is, and she said, you’ll know, and I went in and there was a wall of Veuve Clicquot. I don’t remember anything else about her apartment except she had a Fermor ARC and I said, who do you know to get that? And she said, basically, him darling. I am always craving more of his sensibility, his world. And hers.

Liebling: the other night in Georgetown a professor was quoting his reportage on boxing and I was quoting the old cards on the table at Cafe Loup and we both agreed we should read more of his writing.

Gospodinov: a perk of my work is that my novelist clients are often also professional literary critics, so when Martha Anne Toll says someone is IT, I order a copy.

Kingmaker: I picked this up last night in Greedy Reads. She is in EVERY story about men and power of a certain age. I will need to read this one in the bath at Claridge’s in London (interesting aside: she died while swimming at the Ritz in Paris).

The Life of Kings: I met this author at an event with Gerry Brewster that was connected to his father’s (a Senator who was close with both JFK and LBJ) biography and the three of us had dinner afterward. A journalist of the old school, vibrating with integrity and from an era when a few years in a foreign bureau was just what one needed to make a mark in politics and public service. Let’s bring it all back.

Lauren Cerand is a public relations consultant, reader, writer, and once and future jeweler.