Being Here is Everything: Womb House Books Review

Issue Three: Sofia Samatar's Opacities, Lena Moses-Schmitt visits Paula Modersohn-Becker, Lisa Locascio Nighthawk's "What I'm Not Reading," and Anniqua Rana's relationship with Virginia Woolf

For the third issue of the WHB Review, we are thrilled to feature work by Sofia Samatar, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Lena Moses-Schmitt, Lisa Locascio Nighthawk, and Anniqua Rana. We are looking forward to the third meeting of the Womb House Book Club on September 18th, when we’ll discuss Claire Dederer’s Monsters.

Follow us on Instagram and check our website for announcements and events. Thank you for reading and subscribing!

The Work of the Phantom: Sofia Samatar’s Opacities by Jessica Ferri

I tell my students that writing is a matter of life and death. This belief comes from the writing of Hélène Cixous and Marguerite Duras. Cixous: “To begin (writing, living) we must have death.” Duras: “The only alternative is to say nothing. But that can’t be written down.” This philosophy has been confirmed and amplified by a new book, a tonic, Sofia Samatar’s Opacities: On Writing and the Writing Life.

As Cixous wrote, “The only book worth writing is the one we don’t have the courage to write.” What obstacles rise up for us when we are writing, “who are you,” Samatar asks, “when you are writing?”

Samatar finds herself in “the diversity sideshow,” the “exemplary” writer from x race. “Was it shameful to draw attention to one’s race . . . or what was really shameful was leaving these things out?” Performing representation, “I wondered what I was mourning, what I lacked moving through the fluorescent conference light with my name tag, my paper cup. I realized it was writing.”

“The purpose of avant-garde writing for a writer of color is to prove you are human,” Samatar quotes M. NourbeSe Philip. “I remembered Samuel R. Delany,” Samatar writes, “who said that he was always being asked to speak with Octavia E. Butler, another Black science fiction writer, rather than writers of his own subgenre, cyberpunk, who were not Black.”

Jamaica Kincaid, in an excerpt from a new book on James Baldwin, wrote of her frustration that Baldwin was pulled away from more creative work. “I always feel that his main project, his main impulse, was to write novels, to write fiction, and that this horrible situation—the oppression, the violations of our society—got in his way. And that, I feel, is unforgivable. I feel there is a great artist of another kind that was not allowed to be.”

Opacities is written to Samatar’s friend and collaborator, Kate Zambreno, whose work approaches similar questions. “No one respects a notebook until the writer is dead,” Samatar responds. “It was here that I fell on the notion of posthumous writing.” So many questions demanding biography, personality, even authority. Who is Elena Ferrante? A mask is another way of being removed from identity; it’s a way of living and writing but writing dead. “All books are posthumous, I realized. All writing is ghostwriting.” To Zambreno, she writes: “You told me you tried to write as if already dead.”

“Is it a memoir? Fiction?” an interviewer asked Constance Debré, of her book Love Me Tender. “It’s a novel,” she responded. “Everything is true.” These queries push us away from writing. “We the undersigned are tired of being Black at literary events,” Samatar exclaims. “We reserve the right to have no identity, like Keats.” The terrifying notion of being seen, worse yet, being boxed-in. “The highest desire desires both to be alone and to be connected to all the machines of desire,” Samatar quotes Kafka.

Sofia Samatar writes of freedom. Opacities is a notebook of the endless text, a deathbed confession that stands up and speaks.

“That’s how I want to be seen and how I want the writers I love to be seen,” Samatar writes. “Not for the self but for the ecstasy, the writerly ecstasy, caught and passed on like an electric charge.”

Jessica Ferri is a writer and the owner of Womb House Books.

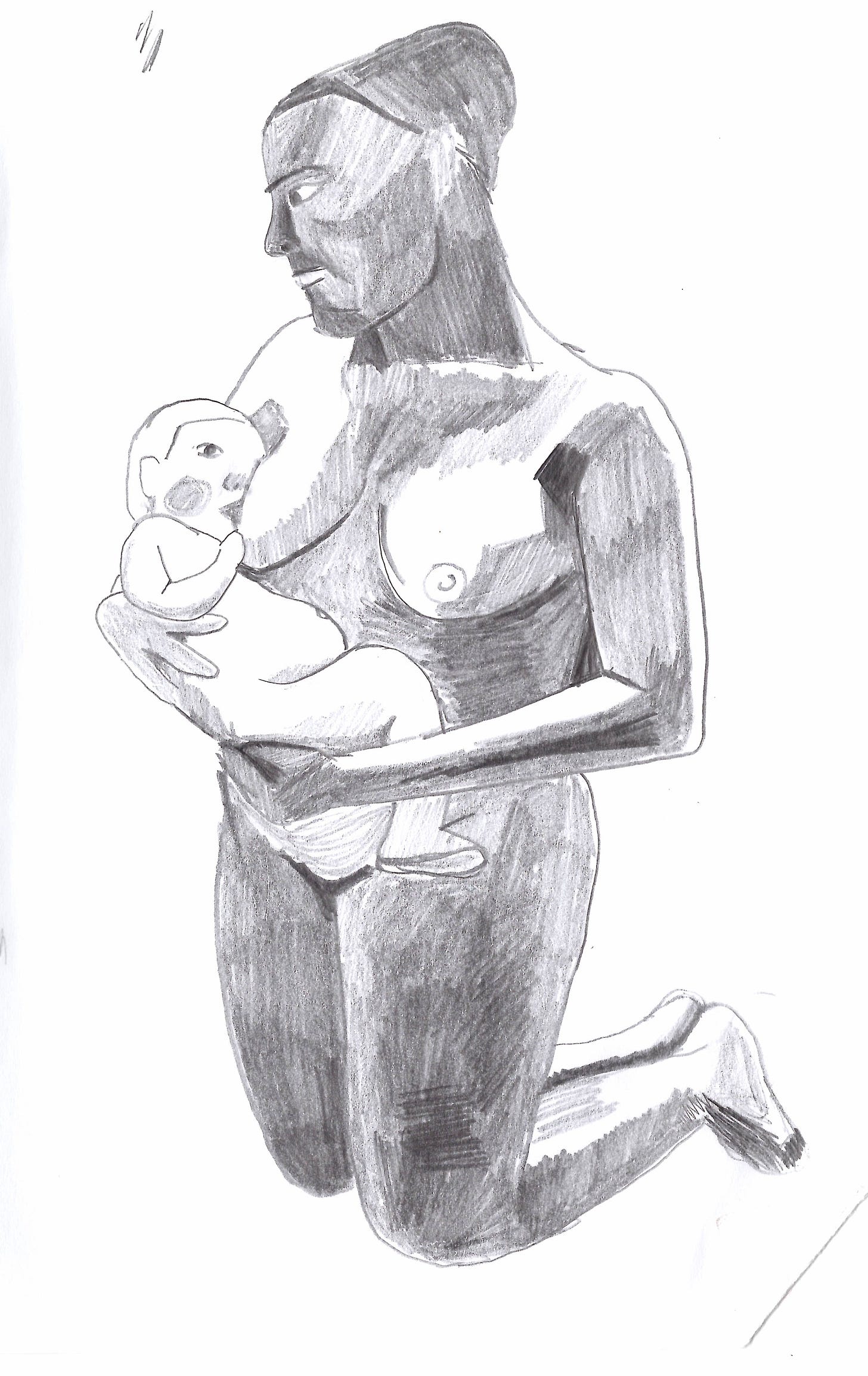

Lena Moses-Schmitt Visits Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907) was a German expressionist painter at the turn of the nineteenth century, and is widely considered to be the first woman to paint herself nude, and to paint herself nude and pregnant. I also love her paintings of women with children ("Kneeling Mother with Child at Her Breast"). Modersohn-Becker died at 31, a few weeks after giving birth to her first and only child, of a postpartum embolism.

Walking through Modersohn-Becker's paintings in the snug rooms at the Neue Galerie, witnessing her eye develop over the years, I got the sense that she saw herself more and more clearly as she grew as an artist—she knew how to simplify her face down to the most important details, colors, and shapes. I once read some critic or art historian say that in some of her self-portraits she barely resembles herself, but I don’t agree—though she paints herself in different styles, almost like trying on costumes or different ways of seeing, there’s a line of consistency that runs through all of them. They all resemble her. Here are some sketches I made of a few of Paula Modersohn-Becker's paintings currently on view at the Neue Galerie in New York as part of the first U.S. retrospective of her work.

Lena Moses-Schmitt is a writer and artist. Her work has appeared in Best New Poets, The Believer, The Yale Review, and elsewhere. She lives in New York.

What I’m Not Reading by Lisa Locascio Nighthawk

The Undying by Anne Boyer

My copy of this book is a first edition hardcover. I bought it when it came out, probably at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino, where I lived then, or maybe at my favorite San Francisco bookstore, Dogeared Books. Boyer had won a Whiting the previous year, and I was curious about her work. I have never read her, not for any particular reason other than that there are too many wonderful writers and not enough time in one life.

When I bought this book, I thought that my mother was in remission from cancer. I didn’t yet know that her cancer had in fact never gone into remission, but had instead dropped its genetic markers and mutated from HER+ Stage II breast cancer to Triple Negative breast cancer. The Undying was published in September 2019, the month when my mother began to precipitously lose her mobility. No doctor, specialist or general, no nurse, and no physical therapist—my parents consulted many—could explain why she was suddenly so overcome with pain that in the space of a month she went from being an independent adult to an invalid who did not leave her bed. Her cancer was discovered in the ER of the Mendocino Coast District Hospital, where she was admitted on arrival to visit me that November for Thanksgiving and my birthday, which is always a few days before or after Thanksgiving. After three weeks in that hospital, my mother was transferred via air ambulance to Chicago, our hometown, where she died of metastatic cancer in February 2020.

The window of time in which I might have read Boyer’s book about her own experience of triple-negative breast cancer with some distance before my own experience with it was vanishingly short. Five years later, I am beginning to feel like I might someday be able to read this book.

Cowboy Graves by Roberto Bolaño

Here’s a secret: I have not read all of Roberto Bolaño’s books. This disclosure feels daring to make, because I am or have been in a previous life a self-styled Bolaño expert. Maybe expert is the wrong word. I am a lover of Bolaño. Between 2012 and 2013, I made three pilgrimages to Blanes, the town on the Costa Brava where he raised his children, where I met Bolaño’s friends, explored his neighborhood, and eventually became the first Anglophone journalist to be granted an interview by his widow and literary exector, Carolina López, because, she said, “I think you are serious about Roberto.” Few authors have made as powerful an emotional impression on me as the melancholy and rapacious Chilean lover of pulp culture. My relationship with Bolaño began when I attended the December 2008 release party for 2666 with Jessica Ferri, or tried to; by the time we got there, all of the tote bags and free drinks were long gone. I have sometimes felt so intimate to him through his work that I wonder about my grip on reality. But—or perhaps because—of this, I have never finished reading all of his books, and I don’t know if I ever will. Even though the publishing industry has been kind to me and brought out posthumous book after posthumous book, I don’t ever want to be done with Bolaño. To have read every word he will ever write is a possible reality I am unwilling to entertain.

Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry

I’ve hauled this book around for decades now, ever since my very first workshop instructor in my MFA spoke about it reverently throughout that semester. He did not give the book’s full name, and he had a thick, musical accent, rendering the identity of this book I had never heard of a further mystery. This man was also the only faculty member not allowed to close his door during meetings with students. He once told my roommate that he would hold her hand if she was scared on a flight to his home country. This year I’d like to finally apply for a scholarship to the workshop named after this book, from which, of course, Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives takes its epigraph. Maybe my avoidance of this novel is connected to my habit of leaving some Bolaño unread. A little terra incognita left to discover.

Siblings Without Rivalry by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish

I borrowed/stole my mother-in-law’s copy of this book as part of an ongoing process of deliberation.

Fairy Legends of Ireland by Croker

The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries by Evans-Wentz

British Fairy Origins by Lewis Spence

I was into fairies as a kid—one of my first online handles was lfaeri—but they jumped the shark when I was in high school. I remember a girl showing up in a cringe sweatshirt that said “Living Proof That Faeries Exist.” Although, as I write that, I realize that what I am remembering is in fact a baby tee that I myself owned and wore freshman year.

When I lived in Mendocino, I had a frightening experience in which I got lost the old growth redwood forest behind my herbalism teacher’s house and had to bushwack my way out with my bare hands. I became so disoriented that I began repeating my name and date of birth. I finally emerged in a field where a man and a woman stood talking and didn’t seem to hear me when I called out to them. I thought I might have time-traveled. My teacher told me I’d been elf-spun.

This year my partner and I have been observing the impact of fairy-type people and fairy-type places on our life. Mendocino is a fairy place; Topanga is, too. Sometimes you get the stink of fairy on you and need to eat dark chocolate and black tar molasses and touch iron. Sometimes something enchanted lures you in just a little too deep. I took these books out of the library at the C.G. Jung Institute of Los Angeles, where I receive analysis. They are overdue.

The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck

I’ve owned this book for years and moved it across the country several times and have heard good things about the author, who is German. My edition is bound in a beautiful forest green cloth, with silver metallic letters on the spine. But the title scares me so I’ve never read it.

Fetish: An Anthology edited by John Yau

Water Tower Place, a high-end mall in the Gold Coast neighborhood of Chicago, was one of my mother’s favorite places, and we went there often. I bought my first copy of this 1998 anthology at the Rizzoli Bookstore at Water Tower when I was thirteen and wanted some smut. I only read one story, Cris Mazza’s “Her First Bra,” about a pubescent-looking adult woman in a dead-end marriage who answers a modeling ad and ends up in a questionably consensual kink scene that becomes her first act of paid sex work. It turned me on. I remembered its denouement—nothing else, not its author or its title—all my life until I bought a new (used) copy this spring, thinking I’d write about it in my newsletter. But nothing in it has held my attention. The exception is a previously unpublished story by the outsider artist Achilles G. Rizzoli, no relation to the booksellers, which I read sitting here writing this, because I thought Rizzoli the artist was related to Rizzoli the booksellers and I was going to include that here. “Baker Betterlaugh Today” is a horny short about three men baking a cake with a young woman: “Unable to avoid her movements, Manlimaid felt extremely uneasy with erectible pressure, sensing allied wetness imminent.”

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

This novel won the National Book Award in 2010. It was published by a small press, McPherson & Company, and although Gordon had been working for over thirty years at that point, few were familiar with her fiction. I became interested in Lord of Misrule because at Western Michigan University, Gordon was a faculty colleague of one of my heroes, Stuart Dybek, whom I was lucky to study with in Prague in the summer of 2008. We kept in touch, and years later he told me about how the surprise National Book Award had turned Gordon’s life around and inspired her to bestow a similar prize on a writer we both knew. I love the magic generosity in Stuart’s story. Although her early novel She Drove Without Stopping is important to me, I have never opened Lord of Misrule.

Lisa Locascio Nighthawk is the chair of the Antioch MFA and the executive director of the Mendocino Coast Writers’ Conference. Her first novel, Open Me, was published by Grove Atlantic in 2018. She writes a newsletter called Not Knowing How.

Patterns of One’s Own: On Virginia Woolf by Anniqua Rana

For now, lounging on the deep green deck chair, nibbling scones and clotted cream, I am at peace, in good company, at home. Around me, full bloomed apple trees abuzz with resting bees. Birds pecking at crumbs after gliding through intense yellow rapeseed fields by River Cam; the quiet hum of families picnicking in the warmth of late May.

Not surprising then, that a century ago, a group of young intellectuals gathered in this space to question patriarchy and promote pacifism, to go skinny dipping, to praise idleness, to write poetry, to discuss the fluidity and ambiguity of language, and to mark out a space of their own— Brooke, Forster, Keynes, Russell, Wittgenstein, and, of course, Virginia Woolf: The Grantchester Group.

Taking another sip of my elderflower spritz at The Orchard Tea Room, I confirm my thought: I belong.

I marvel at my ability to conjure up a feeling of belonging, whether in this Tea Room outside Cambridge; in my college dorm in Pakistan, where I grew up; or in the college in California where I have worked for over a quarter century.

How does it happen? How am I able to eliminate all doubt about why I belong wherever I choose to go?

Only recently have I thought this through. To begin, I ground myself wherever I live. And then, when I reward myself with travel, I read up on places I visit. I seek out all that is familiar to me. I make connections with those who were here before me, at whatever level possible, and I invite them to join my thoughts.

My invitation is like an addition to a knitted garment. At times the extra colors, the extra stitches, the tassels are complementary to the original—but when they distort, misalign, I find other ways to make myself at home.

Rather than building on the previous garment, I begin unraveling the original. I wash the unraveled yarn in warm water, dye it in a color that suits my needs, create a new pattern, a new design, for a scarf, a shrug, or if I’m very ambitious, a sweater to comfort me.

The original becomes a shadow to the reality I create, and that is how I create a space of my own.

This is not an exact science and even as I write this, I remain skeptical to the extent of this strategy. There’s always a lingering doubt. Does my belonging need confirmation? And if so, from whom?

But until I get to that point, I can stretch out, like I am doing here, in Cambridge on the green deck chair, with pigeons pecking scone crumbs at my feet.

Here, I commune with Virginia Woolf.

I open my Kindle on my phone and pull Joanna Biggs into the conversation. Last year, I read A Life of One's Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again, where she seeks out her place among writers like Woolf.

The “British bohemian elite” she says, “…the whole Bloomsbury thing [was] not just distant but also kind of embarrassing, all decorative scarves and elegant dissension.”

And then, she reconnects with Woolf as an adult, and realizes the writer made herself “intellectually formidable because she was angry”. She was angry about the abuse she suffered from the men in her family. She was angry because she did not go to college. She was infuriated by all the restrictions that society had imposed on women.

Her anger is mine!

I don’t know how much Woolf was able to unravel from the past. Her anger seems to have compelled her to pick up a completely new ball of yarn— something aligned with nature— and then she began knitting her stories.

And to save herself from depression, hallucinations, she turned to the craft of knitting. And then you see all the women knitting with her, in her stories: Mrs. Ramsey, Eleanor Pargeter, Miss La Trobe, Lily Briscoe. They all knit to connect.

I put my phone down and think of how I first connected with Woolf forty years ago in graduate school.

I was introduced, but we didn’t engage, not much. It could have been that she wasn’t even interested in connecting with a biracial twenty-year-old in Pakistan.

I know I made an effort. I always did. Anyone who took time to write, be published, and then be included in the curriculum in another continent, in another century, got my attention. They deserved it.

So I diligently read, analyzed, and wrote about To The Lighthouse and “The Death of the Moth” but not much else. “A Room of One's Own” or “A Woman’s College from Outside” would have spoken to me, but I don’t even think they were available in our college library.

And, at that time, the curriculum was not about me. It was about others. It was about what those others expected me to read, and know, and be.

And I learned that lesson well.

—

My primary incentive in being here, in Cambridge this May, is to visit mummy, not to commune with Woolf.

Mummy moved to her birth country, England, a decade ago after living in Pakistan for over fifty years. There, she taught English Literature and founded a school that she ran for decades.

Now, here in Cambridge, she is reliving her past inside herself. Her focus is on her daily existence. When she was young, she traveled the world, and now her mind wanders to those places during the day and maybe even at night, in her dreams.

She taught me to travel, to read, to write, to connect with those before me.

Mummy—when she could remember—interspersed her suggestions for the week with, “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow”, and ended an outing with, “Home, James”, making literary references whenever possible.

She’ll enjoy accounts of my literary jaunts following Woolf. I know. I will also tell her of the few days I spent in a monastery in Spain before coming to Cambridge.

—

Before visiting mummy in Cambridge, a group of us, with two preschoolers, booked apartments at the Convent of Santa Clara in Medina de Pomar, an hour north of Burgos, Spain. Despite our being with our spouses and grandchildren, there is a familiarity in this convent and bakery run by cloistered nuns.

In Burgos, I learn, I can view the earliest known knitted items in Europe, created by Muslim knitters and preserved in the tombs at the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas.

The moors brought knitting from Egypt, where the first knitted sock, on display—not surprisingly—in the Victoria Albert Museum, is considered the oldest socks dating from somewhere between 100 and 350 CE. The toed-red-socks were made not with two needles but with a single large-eyed one.

Somewhere between then and the 1300s, before or after arriving in Europe, knitting became a two-needle craft. I’m not sure if this was an improvement since I am only familiar with the evolved form. I saw photos of the intricately knitted cushion covers online and was interested in seeing the knitted Arabic kufic script, similar to that in the Alhambra.

I’ll tell mummy about all that we see. The stay in the convent, the knitted cushion covers, The Orchard, the Fitzwilliam Museum, a few blocks from her, to see the original manuscript of “A Room of Her Own” with notes in Woolf’s handwriting.

If I have time, I’ll visit Newnham College and Girton College where Woolf delivered the lectures. And before I return to the Bay Area, I might even visit Bloomsbury.

—

I saw it last fall at Kepler’s Bookstore in Menlo Park, and I couldn’t resist. The World of Virginia Woolf 1000 Piece Puzzle, with its multi-storied buildings of the 1920s and 30s, with living quarters below and servants’ quarters in the attics.

The places in Woolf’s life and work are familiar. They push on my memories of England in the 70s when I lived there as a child. The double decker, the dome of the Botanical Kew Gardens, St Pancras Church.

And King's College Cambridge, a short walk from where mummy is now.

I look closer at Hogarth Home, Richmond— where mummy went to school— “The Wasteland” was published there and so was “Kew Gardens”—where we had picnics. The British Museum, where we saw the King Tut exhibit.

This time, I think, as I look at the puzzle, when I visit mummy, I will take a self-designed Virginia Woolf tour.

But before that, I have gaps to fill. I haven’t returned to Woolf since graduate school. I start with her journals, then Gill’s biography, Virginia Woolf and the Women who Shaped Her World. I re-read To the Lighthouse, some short stories, whatever my busy schedule allows.

I know of the genius, her mental illness, but my reading uncovers more: the abuse by her brothers, her resentment of not going to college, the likelihood of her great-great-maternal grandmother being of Indian descent—I don’t think she knew that either.

She was judgmental of friends, a classist and racist who wore blackface.

And she sought peace and sanity through knitting: “the saving of life.”

And then my browsing history guides algorithms to bring up more. I learn about the International Conference on Virginia Woolf at Woolf College, University of Kent in Canterbury. During the conference, participants knit and crocheted squares and other shapes, and joined them together to cover an armchair, serving as the centerpiece of the event.

And the more I read about Woolf, the more my iPad directs me further. In articles about hypochondria and suspense, in places I least expected her to be referenced, and I realize how relevant she has made herself to the western world, the impact of her anger.

And then Edward Albee takes over my feed—unhappy marriages, dysfunctional academics, angst, the unexpected fear of Virginia Woolf.

After reading all this, I return to the peace-inducing and life-saving craft of knitting. The casting of stitches; the knit-one-purl-one of a border; the slip-one-knit-one-pass-slip stitch-over of the design; the weaving in of other colors for argyle; the twisting of cables; the casting off for the neck — the recasting to connect the pieces together.

The building of a comforting sweater.

And then, like me in my college days, you weave colored silk ribbon into the holes you created to balance the stark whiteness of the yarn. As a teenager and young adult, in Pakistan, I knit often, mainly sweaters for myself, despite a small window of winter to wear them.

Unlike my college curriculum, I rarely follow knitting patterns. I would like to believe that instinctively I create works of knitted genius. I have only a couple photos to prove otherwise. But I wore those sweaters with pride. My own creations.

—

It’s 5:00 am, jet-lagged, sipping coffee looking out at the empty fields around the convent. The walls are ancient. I sit on modern outdoor furniture in the verandah on the second floor, looking out at the opposite side of the building stylishly retained as ancient, deserted, whispering a past that I will never know.

The others woke earlier, talked for hours, and by the time I get out of bed, they are already heading back to bed to catch a few hours of sleep before the day actually begins.

I open my phone and check my reading list: the unfinished article about suspense in To the Lighthouse, the reader “wanting to know what happens next.”

I wonder about my suspense for this trip in Spain. Will we get to see those intricately knitted cushions with Arabic calligraphy?

The suspense of knitting a sweater, I think. Will a sweater ever be finished? If I drop a stitch, will I be able to pick it up before it unravels back to the border?

Did Woolf think of that? Creating suspense? I sense none in “A Woman’s College from Outside”, just flickers of thoughts, broad brushstrokes of how the young women think of their lives, present and future.

I look at the empty rooms below me and wonder if Woolf had come here, to Spain. A quick Google search shows she came for her honeymoon to Granada. I wonder if she wrote anything about her trip.

I could check, but I choose to flip through A Life of One's Own by Joanna Biggs. I read about how Woolf’s body, wrapped in a fur coat, is found by some kids twenty days after she drowns herself.

The church bells chime. They keep chiming. Otherwise, it's quiet.

The first "twenty-four dueñas de velo prieto”—nuns with black veils— joined this Monastery of Santa Clara, founded on January 11, 1313. Did the nuns with black veils make this a place of their own?

The day before, we purchased Buñuelo – Fried dough balls, Churro, Macarons, from behind a closed revolving window.

My sister speaks Spanish, so she takes care of the whole transaction. We see no one, but we enjoy the baked goods.

Their prayers, their pastries, their Airbnb. Is this what Woolf meant about a room of one’s own? Financial security is definitely part of it.

As it turns out, the grandkids don’t take to museums, and since my interest in family far outweighs intellectual pursuits, we decide to put off the visit to ancient knitted artifacts for another trip. Prehistoric caves and a trip to the beach in Santander are far more appealing.

—

“The wind of the Cambridge courts” went “neither to Tartary nor to Arabia, but they lapsed dreamily” over the hostel roof of Lahore College for Women, a century old Women’s college whose graduates include national political leaders, artists, human rights activists, and religious aficionados in South Asia, my Alma mater.

At that Women’s College, Mrs. Ramsey turns up knitting brown stockings for the lighthouse keeper’s son. She preserves her own son’s hopes of a visit to the lighthouse. The caring, knitting Mrs. Ramsey stays with me. Her narcissistic, self-centered philosopher husband does not.

“A Room of One’s Own” would have been so relevant to the male-dominated universe of that time and place.

I text my college roommates on WhatsApp in the “Lost and Found Friends” group to ask what they remember of Woolf. They all live in Pakistan.

“Kon? (Who?) one responds in Urdu.

She made no impact on our lives back then.

We could have joined Woolf in her anger on many levels, but we didn’t. Would that have disappointed her or were we not her intended audience?

We see our all-women's college in her piece: “a place of seclusion, or discipline, where the bowl of milk stands cool and pure and there’s a great washing of linen”.

There was definitely seclusion and discipline, and a great washing of linen at that time in between the reading Woolf. But the memory of that reading has disappeared.

As girls, as women, we were insiders—inside the home, inside our own minds, inside our intricately knitted groups that we knit, undid, redyed, and redid, to strengthen, to endure.

And now, for the past decade, I’m a college administrator, that “Elderly [woman], who would on waking immediately clasp the ivory rod of office.”

Woolf didn’t know me, but she knew my life, and so I’ve made my decision.

If Woolf were sitting on a green deck chair in The Orchard, undoubtedly, she would not invite me to join her. However, I cannot ignore the impact of her work.

I will, therefore, be adding a slip-one-knit-one-pass-slip stitch-over to her pattern and make it my own.

Anniqua Rana’s debut novel, Wild Boar in the Cane Field was shortlisted for Pakistan’s UBL Literary Award 2020. She co founded the blog Tillism طلسم – Magical Words from around the World. Her writings on travel, gender, education, and books have appeared in Rova, TNS, Naya Daur TV, International Education, Ravi Magazine, Bangalore Review, Fourteen Hills, The Noyo River Review, Delay Fiction, Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in Education, and other publications. Her doctorate in International Education focused on the implications of technology for women of Pakistan in higher education. She has taught at San Mateo Community Colleges, University of San Francisco, Lahore University of Management Sciences, and Stanford University. She travels, writes, and lives between California and the Potohar region of Pakistan.