Welcome to the first issue of the Womb House Books Review!

We are a feminist bookshop founded by Jessica Ferri specializing in 20th Century Literature by women, queer authors, and writers of color. After nearly two years online, we are thrilled to announce we are opening a brick-and-mortar location in Oakland’s Temescal Alley on Saturday, June 15th.

Our first issue contains a conversation with Sheila Heti on her new book Alphabetical Diaries and more, “What I’m Not Reading” with bookseller and translator Claire Foster, a report on the Persephone Books Festival from Molly Brown and Christine Jacobson, and a Q&A with Heather McCalden on her new book The Observable Universe.

Interested in submitting to the WHB Review? We are looking for work on books by women, queer authors, and writers of color. Drop us a line at wombhousebooks@gmail.com.

Subscribe for more books coverage and announcements from Womb House Books!

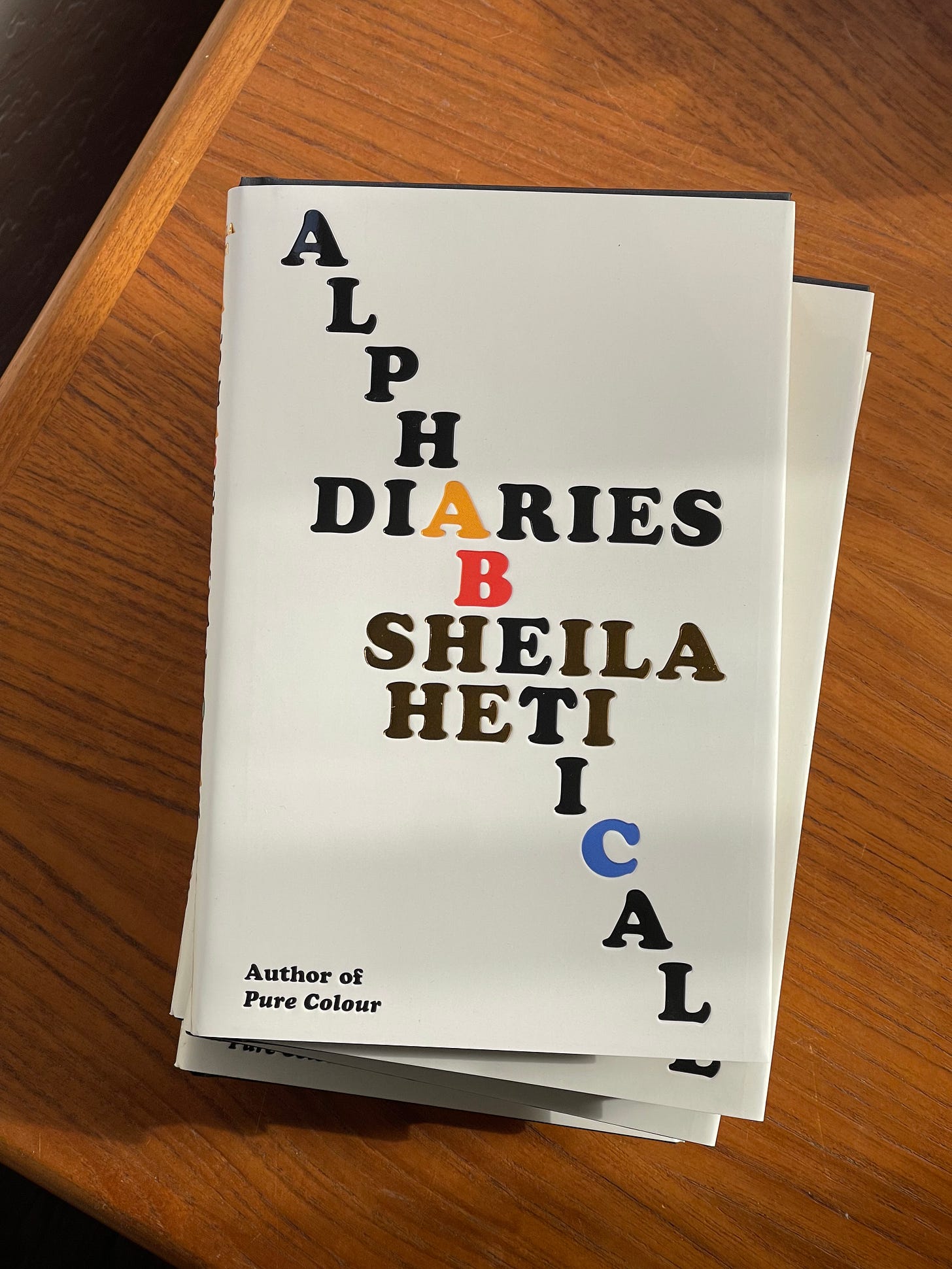

A Conversation with Sheila Heti

Back in March I had the pleasure of speaking with Sheila Heti via zoom about her new book, Alphabetical Diaries. What follows is an edited and condensed version of that conversation.

I first met Sheila back in 2010 (!) when I interviewed her about How Should a Person Be? for The Awl. Since then, Sheila has published many other books, including Motherhood and Pure Colour. In 2010, I wrote, “I don’t know a single person who wouldn’t benefit from reading Sheila Heti’s new novel,” and fourteen years later, this is still true. —Jessica Ferri

JF: I read Alphabetical Diaries as more of a novel, or an art-piece, than a memoir or diary. The fact that it’s alphabetical… The title, also… These things help me to understand it as an artwork rather than your actual diary.

SH: That seems right. You know, it was hard for me to choose the exact title of this book. Should it be Alphabetical Diary? Alphabetical Diaries? The Alphabetical Diary? I just couldn’t figure it out. I was asking everyone, and I finally asked Na Kim what she thought. Na was the one who was going to be designing the cover, and she also designed the cover for Pure Colour. She said, “well if you don’t use “the” then the title itself is in alphabetical order.” She cracked the code! So that’s what I did. Now even the title follows the rule of the book.

JF: I love that you included her in that decision. Most people probably wouldn’t think about that when it comes to a title! At one point that title was Canals.

SH: Yes, a long time ago and for many years. I was thinking about, like, the canals in the brain. The ruts, like water running through canals; the idea that our thoughts travel the same paths over and over. But then one day I saw it written down and suddenly I noticed the word “anal” in the middle and I thought, I don’t want ANAL on the cover of my book!

JF: Yeah, I don’t know about that anal situation . . .

SH: Once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it. Alphabetical Diary was always the working title of the book, and often the working title becomes the title, and I don’t mind, because I love the blandness of working titles. I love when paintings are called Woman in a Hat, or Three Dogs or Apple and Flowers. I like a certain artlessness in a title.

JF: I think the “I” chapter is the longest, which makes sense. One of my personal favorites was the section that just repeats, “I told him…” Or, “Hanif told me…” “Hanif said…” “Hanif said…” The repetition is almost like a Zen koan. It’s like a chant, and it makes you realize how much you’re doing the same thing over and over again in your life.

SH: Yes. I actually think I couldn’t have written this book as a younger person because I was too nauseated by the idea that life is repetition. When you get older, you accept that life is repetition, and you start to relish repetition, and you find the joy and beauty in it, and the small variations in it are really what life becomes, about rather than the humongous changes and differences year to year. I think, if I’d had the material and had the idea ten years earlier, I couldn’t have written this book. It would’ve depressed me too much to see how static–not static–but how much of an outline there is around oneself. When you’re young, there’s this boundlessness about who you can be or what you can become, and that narrows as the years pass, and unless you start to find it sweet, it’s very depressing I think, to live. I did find a way to find it sweet, and therefore I was able to make this book, and make it seem like there is something sweet about life. That there’s something good about it even if there is all this repetition.

JF: The parts of the book that involve other people are more funny to me than anything else, because they are so true to life, in terms of communication difficulties. But I found it to be really inspiring on a spiritual level: the constant hum of creative work and creative activity that is going on in the mind of a writer. I find that fascinating and wonderful. There’s this idea that a work of art emerges and is perfect, but I think the diaries give you a glimpse into a process that is sacred.

SH: Right, it’s not the final book that’s the work of art, but the process of making it, and it’s fun to show that process. I think the diary is so much about that, and it can be, whereas most books have to be just the outcome, the evidence, of the work that went into it. But the process is when the artist you’re connecting to God or the universe, and when the book is out in the world, your connection to it is severed; the art leaks away.

I think it’s nice for books to appear effortless, though—to seem like they came easily and naturally. That’s part of their beauty. It’s like watching a ballet. You don’t want to see the effort. I mean, I sometimes love going up close at the ballet: you can hear the dancers breathing, and you can see the real expressions on their faces, and you can hear the thump of their shoes, and you’re like, “this is hard work, they’re doing athletic work!” That’s fascinating. But the illusion that they aren’t doing any work is what’s inspiring. Most art aspires to the illusion of effortlessness, and I guess the Diaries book does, too. It doesn’t read like fourteen years of frustration and editing. But I’m glad the words can so much be about the effort that goes into making something.

JF: Some of my college roommates were ballet dancers and they would soak their feet, and I would look at their feet in horror, and I would go to the dress rehearsals, and exactly–the sound–it’s almost like horses! Really muscular, moving across the stage, and the sweat! I think it’s Walter Benjamin who said that the book is the death mask of the project. The book is the writer writing the book.

I’m a big underliner, and I actually made these little notecards from the book, that are like mantras that I love: “All my work is so pleasurable these days.” When the book first came out, I was at a party and I was explaining to her what Alphabetical Diaries was, and I was like “It’s like a bible. It’s like the bible. It’s the bible of art.” And that’s really how I feel about it!

SH: Thank you! I’ve always been jealous that I didn’t write the Bible!

JF: Particularly after reading Pure Colour, I started to think of you as a spiritual writer, a writer who is questioning where is God or what is God. Do you consider yourself to be a spiritual or religious writer?

SH: As I get older, the longer I’m alive, the more I feel the strangeness of being alive. When I was younger, I was more preoccupied with other humans and the social world, but now that I’m older I’m more interested in the question of what is life or being at all. I have less anxiety about being among people. I’m grateful for this change, because those anxieties when I was younger were more painful. What I feel now is more like awe and wonder. I prefer my forties to my twenties and thirties, when it was so much about other people.

JF: One of the lines in the diaries reads: “People need personalities to go with the books, but nobody knows who I am, so no personality can go with the books.” Do you feel like this book reveals who you are?

SH: When I wrote that sentence I’m pretty sure I was working on How Should a Person Be? and thinking a lot about Andy Warhol and persona. I thought a lot at that time about how if you didn’t ever see a picture of Andy Warhol, or know about the Factory, or ever read an interview with him, and you just saw his paintings, you wouldn’t understand them. You wouldn’t know what they were trying to do, and you wouldn’t know how to relate to them, exactly. But the more you know about Warhol, the Factory, and the way he presents himself, and his aesthetic, and his philosophy, the better you understand the art. Is that only true of visual art—especially contemporary visual art? I’m now thinking of Jackson Pollock—knowing how he painted his canvases. Or is that also true for writers? I don’t know! I could read Crime and Punishment—and I did—without knowing anything about Dostoyevsky, and it felt complete. But maybe in the contemporary world it’s a little bit different. Under what circumstances do we need to know who the artist is in order to care about the work?

It’s something I was thinking about a lot when I was writing How Should a Person Be? And I may have written that particular line after my American editor rejected the book, saying, “no one knows who you and Margaux are. Why don’t you become famous first and then you publish the book?”

JF: What!

SH: Yes, this was obviously before what we now call “autofiction,” and the autofiction boom. He said, “Who cares about you and Margaux? Why would anyone want to read about you two? And if you’re calling the characters Sheila and Margaux, then it’s not a novel.” Things like that. There was a lot of confusion from him.

JF: That goes against the grain as to why anyone would ever read fiction . . .

SH: I don’t think he understood it as fiction.

JF: We have a few questions from the audience, the first one being: I wonder if Sheila and Sarah Manguso ever chatted about their process? Sarah’s Ongoingness and Sheila’s book are both based on their diaries, but are not their diaries. I’d love to know if there is a backstory of those two brilliant minds.

SH: Sarah and I met at Yaddo in 2006, and she and I remain good friends. I’ve read some of her actual diaries and I’m such a fan of them. I really want her to publish them. I think she’ll probably publish them posthumously—they’re probably too personal and gossipy to be published now. She’s actually one of the people I most wrote Motherhood towards. We had this silly pact that we’d both have children, and I guess I backed out.

Anyway, we’ve have many conversations about all sorts of things. We kept even a diary together at one point. We were both Googling ourselves too much—maybe we both had just published books—and our solution was that we had to write in a Word document every we Googled ourselves. We had to write what we found online, where we had googled ourselves, whatever our thoughts were before we did it, and how we felt after. And at the end of each month we would send each other that month’s Google diary, as a sort of penance, or humiliation. I guess it was also a way of making this unconscious tic something conscious, in the hopes of getting past the urge.

JF: She just published her first novel, what, two years ago?

SH: Yes, Very Cold People. I love that book. I’m the one who told her to write a novel! She said she never would have written this novel if I hadn’t been begging her to. For years I’ve said, “Sarah, write a novel!” And she would say, “I don’t know what that means.” And I would say, “It can mean anything! I just want to read a novel by you.”

JF: Good job, Sheila!

SH: Yes, it’s one of the good things I’ve done in the world.

JF: There’s something so intimate about your books, even when they aren’t exactly about you; there is a sense of disclosure. How do you then decide that material from your life can turn into a book?

SH: Hm. I think I really want to keep my books alive for myself for when I’m writing them. I don’t plan the end of a book. I know the texture, the color, the atmosphere, but everything else is pretty much open and unknown. It’s very alive to me. Because of that, I think I participate in it more, and my days come into it more. Because if I was just to use my imagination to map out a book, there would only be a part of my mind that was participating—the part that imagined it at one moment in time, and the part that is the imagination. But if what I think the book is is changing every day, there’s this constant dynamic between the book and whatever I’m thinking about or doing in my life, and it’s really alive the whole way, and I want it to be alive for as long as possible.

JF: It’s refreshing to know that there’s so much freedom there.

SH: I do it that way because it’s fun.

JF: It should be fun!

SH: It’s more interesting that way.

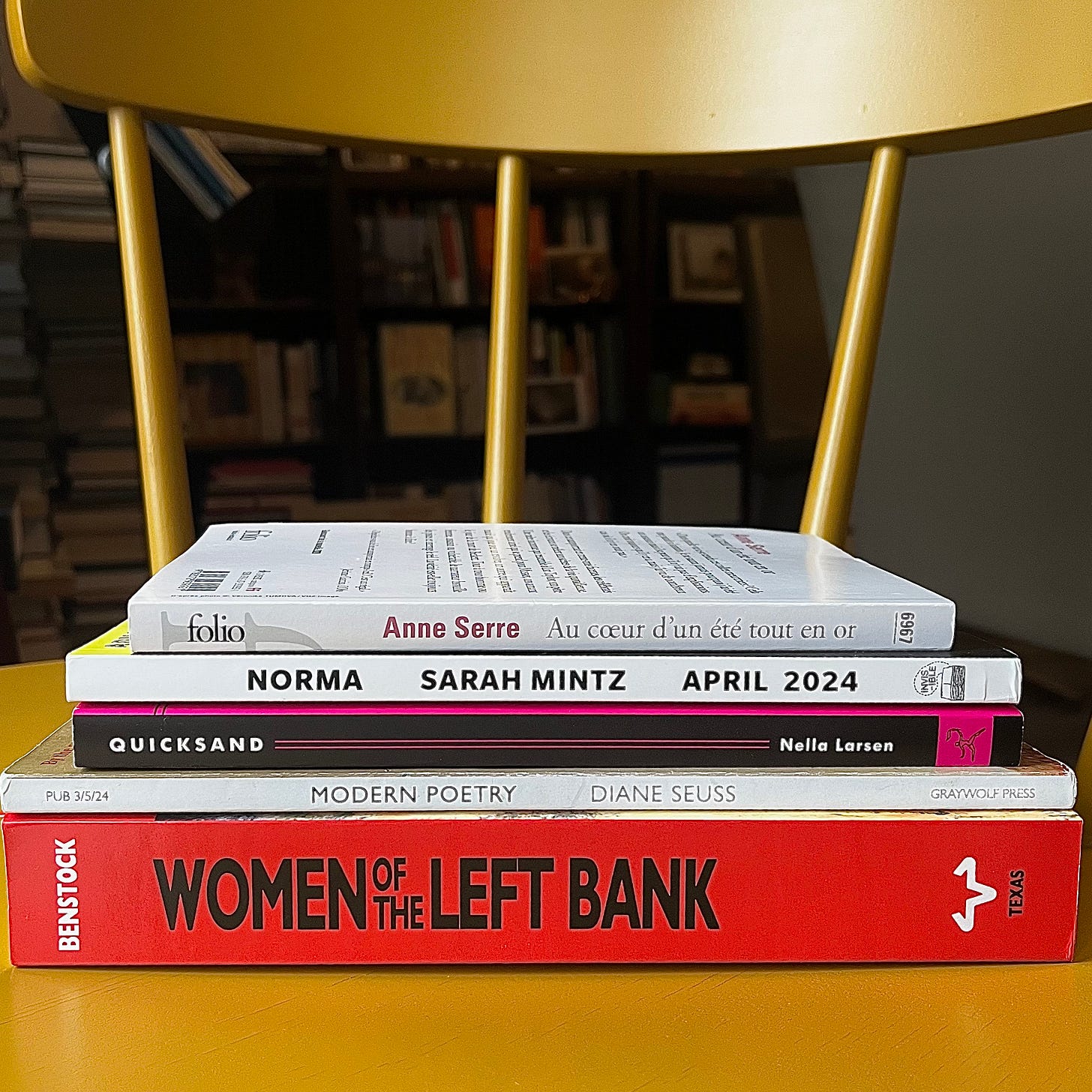

What I’m Not Reading: Claire Foster

To offer a list of books I’m not reading might give you the wrong impression: it might suggest that my unit of not-reading is the single book. But I am drafting a theory of not-reading and its organizing unit is the stack.

I don’t mean a “TBR stack,” which is a phrase I hear wielded by customers at the bookstore all the time; the acronym arises when there is, in question, a book that ultimately cannot be bought because there already exist in someone’s apartment three or four or fifteen unread books.

I could misread this prompt—am tempted to misread this prompt—as an occasion to write about five or six hundred books I’m not reading. At the time of this writing, it’s possible for me to say: I am currently not reading all books.

I spend a lot of time making and unmaking stacks. To make piles out of books and choreograph their mood-movements between my two rooms—I do this more often than I read.

To write about the books I’m not reading is to press against the possibility of writing forever.

Norma by Sarah Mintz (from a stack of galleys): I am the manager of an independent bookstore called Type Books, in Toronto, which means that much of my not-reading has to do with books that are not yet released. A bookseller understands not-reading better than anyone: she is an active not-reader, though she knows deeply, and dreams about, the covers of books and the colors of their spines. Norma is being published this spring by a Canadian independent publisher, Invisible Publishing, and I’ve been hooked: the first sentence of this book is “The older I get, the dirtier I feel.”

Quicksand by Nella Larsen (from a stack of books written in the 20th century or earlier): I bought this book a few months ago at Source Booksellers in Detroit. It is a hot pink paperback, and is placed atop a newly formed stack, which was built in response to my bad habit (also a bookseller thing) of reading mostly contemporary books. “You already belong to your time” is a line that comes from one of Lydia Davis’s essays on reading, and I am trying to remember it.

Women of the Left Bank by Shari Benstock (from a stack of felt urgencies): I bought this book after hearing it mentioned by Lisa Robertson on a podcast; she was crediting it as having been very important to her in the 80s. I want it to be important for me, too, so I don’t read it—I save it.

Modern Poetry by Diane Seuss (from a stack with a secret music): I still have not finished reading her new collection, though several months before the book was published I wrote Graywolf a pleading email, asking to obtain an early reading copy, which of course they sent to me without much gravity, for I am a bookseller, and it is their job to send books as much as it is my job to (not) read them. The day the finished hardcover copies arrived at the bookstore I nearly cried: I’d ordered a big stack, but did not, and still do not, want to share her. It pains me to admit that others can read her. I have read the book’s beginning several times, especially the poem called Colette that begins with the line: “I went through a Colette stage, did you?” And later: “Stack your books on a small raw wooden table / you found in a sweet potato field crawling with snakes. / Chéri, The Last of Chéri, Gigi, piled on a confiscated table.”

Au cœur d’un été tout en or by Anne Serre (from a stack of books in French, on a stool beside my bed): Anne Serre’s books are short, which makes it more likely for me to read them, but I haven’t read this one yet. This one resides inside a stack of books in French, which is intended to impel me to read aloud in French to myself before bed. But I sleep with more ease than I read.

Claire Foster reads, writes, and translates from French. She also works as a bookseller at Type Books. Born and raised in Ohio, she currently lives in Toronto.

Molly Brown and Christine Jacobson Attend the Persephone Books Festival

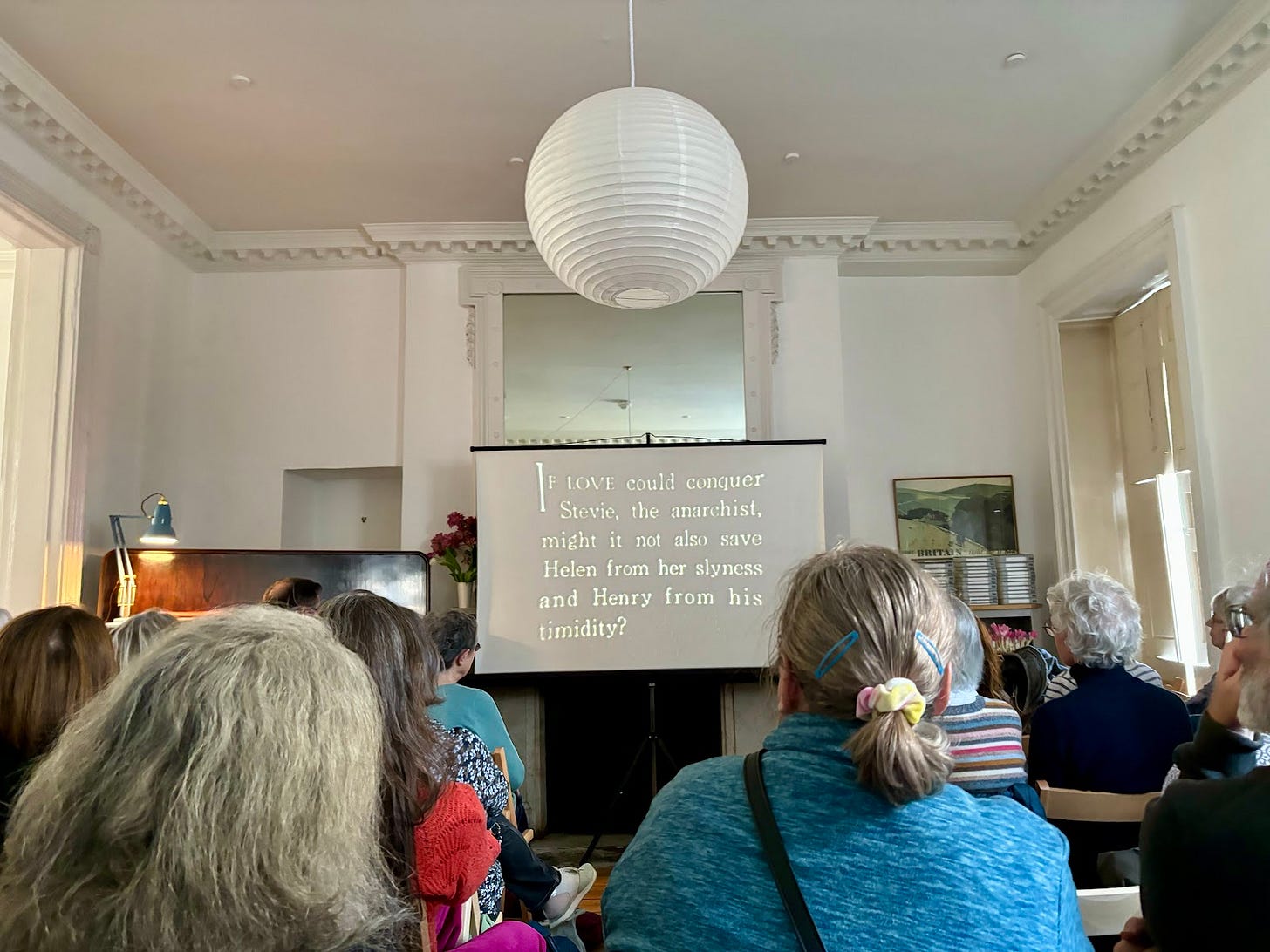

This past April, the British heritage publisher and bookshop Persephone Books celebrated its 25th anniversary with a festival in Bath. The firm publishes out-of-print and unpublished works, mainly by women, and since 1999 has published 150 titles. Along the way, they’ve established a fiercely loyal community of readers–The Observer once described them as the nearest thing British publishing has to a cult–over a thousand of whom descended on Bath to attend a smorgasbord of forty-two curated lectures and discussion sessions. We were invited by Persephone to host one of the sessions and accepted with pleasure. This is our dispatch from the festival.

1. Upon arriving in Bath, all festival-goers were invited to stop by the Persephone Book shop to pick up a signature Persephone festival clutch and badge. We picked up much more, lining our suitcases with Persephone books, scarves, pencils, and totes. The shop exclusively sells Persephone books, printed uniformly in soft dove gray covers with bright reproductions of vintage textile endpapers inside. The store is also decorated with mid-century travel and wartime posters, and flowers spilling out of vases are to be found on every surface.

2. Persephone Festival organizers popped up a thoroughly outfitted tea room in Bath’s Assembly Rooms as a third space for the attendees to commune and unite in Persephone sisterhood. Tea and cake were each one pound, and those who partook were greeted with a table clothed in gingham and tulips boasting the latest copy of the Persephone Biannual. For many festival-goers this was the first time to enjoy a larger community with which to exchange favorite titles and their stories of discovering Persephone Books. As if the details of the room were not enough, the cafe scenes from the 1945 film A Brief Encounter were projected for additional ambiance.

3. Founder of Persephone Books Nicola Beauman opened the festival by giving remarks on how she got her start in publishing, what qualifies a text for the Persephone imprint, and her conception of “domestic feminism,” a post-second-wave feminist ideology that celebrates equality between the sexes while relishing rather than eschewing the domestic arts. This concept is a throughline of many Persephone novels.

4. As evidenced by the crowd pictured here in the historic Bath Assembly Rooms, we suspect Persephone’s best-selling author Dorothy Whipple is on the cusp of a revival. Tickets for this session, titled “Wild for Whipple,” sold out in less than two and a half minutes. The speakers who included novelists Rachel Joyce, Harriet Evans and Lucy Mangan discussed Whipple’s oeuvre and what rival heritage publisher Virago got wrong when they dismissed her as too middle-brow. For anyone looking to dive into their first Persephone novel, we recommend Whipple’s High Wages (originally published in 1930) about a young woman in Northern England who goes from drapery shop girl to owning her own dress shop.

5. Each evening of the festival, in the room just above the Persephone Books storefront, a salon music concert was held. We attended the first evening and were offered champagne and cheese straws upon entry to pair with the music of the Limáni Trio who prepared a program of Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák. While you might think salon concerts extraneous to the literary labors of Persephone Books, the spirit of community the salons ignited and the depth of artistic appreciation they evoked are a reflection of the spirit of Nicola Beauman and the greater Persephone community.

6. Just beyond the checkout of Persephone Books you can see the cozy chaos of the workspace of the Persephone Girls (which is what Nicola and others call Persephone Books employees). An unexpected treat for us was to enjoy this exclusive space as the green room prior to our presentation. Along with a chat with walking book club leader Emily Rhodes, we were fortified with mint tea, ginger biscuits, and cardamom buns from the local bakery. The whole experience put into even greater relief the kindness with which Persephone employees put domestic feminism into practice.

7 and 8. Our session, “Working Women in The Home-Maker” explored domestic labor and women who work outside the home in Dorothy Canfield Fisher’s 1924 novel whose main characters reverse traditional gender roles after the husband is paralyzed and must stay at home raising the children while the wife goes to work at a department store. We also shared our experience leading a working women-themed Persephone book club at our local Beacon Hill Bookstore in Boston. Over seventy attendees joined our session and were treated to dramatic readings of our favorite passages, major themes surfaced by our book club, and a packet to take home including a button featuring The Home-Maker’s endpapers and a design-your-own shop window activity. As the photo demonstrates, we had a lot of fun!

9. The final event we attended was a film screening of the 1925 silent film adaptation of The Home-Maker (which was paired with madeira and cheese straws). Film director James Bobin, who introduced the screening, surfaced the film’s original accompaniment sheet music from the Library of Congress and enlisted pianist Jim Godfrey to play it live with the film. This meant that The Home Maker film would be screened as originally intended for the first time in just under one hundred years. We were moved by how well the film captured the emotional beats of the book and valued the screening as a poignant close to our Persephone Festival experience.

10. Other sessions we attended included one on the selection and designs of the Persephone books’ endpapers and another on the “gentle art of domesticity” by Jane Brocket. As a celebration of the cookery books in the Persephone catalog, Castle Farm in Midford hosted a supper club using recipes from Persephone Books and wowing diners with delights like sorrel soup and trifle. While the murmurs of cozy chatter and cries of delight during the supper club aren’t recorded, many of the sessions have recordings available to listen to until May 22. Here are some great sessions to start with: The Rise of Heritage Publishing, How to Make a Persephone Book, and Nicoloa Beauman in conversation with Eliza Day.

Christine Jacobson is Associate Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Houghton Library where she helps steward the papers of writers such as Emily Dickinson, Louisa May Alcott, and Jamaica Kincaid. Her writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Perspectives on History, and Fine Books and Collections magazine.

Molly Brown is the Reference and Outreach Archivist at Northeastern University’s Archives and Special Collections where she facilitates research and educational experiences with records from Boston’s neighborhoods and social justice organizations as well local news organizations such as the Boston Globe. Outside of work she is a proud member of the Barbara Pym Society, and is always looking for a fellow Shirley Hazzard or Laurie Colwin fan.

Heather McCalden’s The Observable Universe

I had just finished moderating a panel with Maggie Nelson and Miranda July at the LA Times Book Festival when Heather McCalden walked into our booth for Womb House Books and placed her book in my hands. The human brain, apparently, wants to put things into categories, and give things names and labels, but The Observable Universe resists this in a profoundly beautiful way. I’m so glad Heather walked into my life, and that this book is in the world. —Jessica Ferri

JF: When did you know "The Observable Universe" was a book?

HM: The long answer:

A year out of completing my MA degree in photography and performance at the Royal College of Art I should be making visual art to legitimize myself professionally. As a means of jumpstarting this process, I began to research the ideas occupying my thoughts, which at the time revolved around the metaphor of “going viral.” Eventually I generated a ton of textual material, but my visual sensibilities had yet to be activated. I figured the solution to this was to broaden my area of research, so I began investigating virology, biological viruses, and metaphor hoping more information might stimulate imagery to form in my brain. While all this was going on, a small part of me acknowledged that I was looking into viruses and “going viral” because my parents had died of AIDS. Then I read a line in an LARB essay that made something click for me, “we talk about virality not just because the world is interconnected or overpopulated; we talk about it — or, at least, we first talked about it — because of HIV.” Once I read these words, I understood I was using this project to work out my grief. I also realized visual imagery was never going to appear because what I had actually been doing, for about a year, was writing a book. I was just in complete denial about it.

The short answer:

A little over a year into the process, which lasted around six years.

JF: At any time, had you taken a more traditional approach?

HM: A traditional approach was never an option for me because of how trauma has reengineered my brain. A story with a typical beginning, middle, and end structure just doesn’t feel possible because it implies narrative causation which, if you’ve experienced trauma, becomes mentally very abstract. I am, however, able to capture ideas, or catch feelings within fragments.

JF: What drew you to this format?

HM: For a long time I was deeply troubled by the fact that I could only seem to write in little pieces. It felt like I was writing from a place of injury rather than health, and I interpreted this, wrongly, as a weakness. Despite my frustrations, I kept working, and slowly, very slowly, I just came to accept that this is who I am and what I can do in this format. Fortunately, writing and literature are flexible enough to encompass multiple types of expression despite the fact we only champion a few.

While I was coming to terms with this, a strange thing started to happen, or at least it was strange to me. It seemed our contemporary experience of information processing mutated into one of fragmentation. This is even more pronounced today: when we’re online, we’re zigzagging across multiple browser tabs, plucking details or facts, from one page, and merging them with another, to form some aspect of experience. If we’re scrolling, we’re necessarily montaging one image, one story into the next, and so, at the end of the day, our whole understanding of the world is founded on these tiny, decontextualized, electronic splinters.

While writing the book, I became very fascinated by this emerging Venn diagram – the one of my mental state (molded in part by PTSD), and the one of culture (arguably, also molded by PTSD).

JF: How do you feel about the book being described or labeled as a memoir?

HM: It’s weird to me that you can find the work of Prince Harry and Elon Musk in the same section as The Observable Universe, which is to say: I don’t find the label particularly accurate. However, I wrote the book deliberately to suit a new (literary) space, one more reflective – and potentially truthful– to our current moment; we live in genre-defying times where most labels collapse, refract, or slip off their subjects. Because of this, I do extend empathy towards whoever made the executive decision to classify the book as a memoir.

JF: How do you feel, now that the book is in the world?

HM: Not long ago I read this quote by Polish film director Krzysztof Kieślowski that totally floored me:

At a meeting just outside Paris, a fifteen-year-old girl came up to me and said that she'd been to see [The Double Life of] Véronique. She'd gone once, twice, three times and only wanted to say one thing really - that she realized that there is such a thing as a soul. She hadn't known before, but now she knew that the soul does exist.

Though my little book is nowhere near Kieślowski or his film, I’m hopeful that it can maybe help someone not feel so alone now that it is in the world.

JF: What do you want readers of your book to know about writing this book?

HM: The book tells you how to read it and teaches you how to read it as you go along. If you’re willing to engage with its premise – which is simply that the book behaves much more like a record or music album than a “memoir” or “story” – you’ll have a very different experience of reading.

Also: the book has a Spotify playlist!

https://soundsoftheobservableuniverse.squarespace.com/

JF: What question do you wish someone would ask you about this book, and what would your answer be?

HM: During my book tour, my conversations partners have asked fascinating questions based on deep engagement with the text, so I’ve never been left wanting. For example, Rosecrans Baldwin author of Everything Now: Lessons from the City-State of Los Angeles asked me the following, “At one point you cite someone talking about the internet being a collective hallucination. And right now we’ve got these AI language models hallucinating. Solve it for us once and for all: Is the internet alive? Also, what is your relationship like these days with the internet—how is it going, are you guys in couples counseling, etc.”

I responded by saying I didn’t think the internet was currently alive by our human definition of life, however, it might have feelings of its own that are, at present, totally incomprehensible to us. As an integrated network, there is potential for a sort of experience to emanate from the internet, but is that consciousness, is that life, who’s to say? This concept is explored much more thoroughly by Neuroscientist Christof Koch and proponents of IIT or integrated information theory.

In terms of my own relationship with/to the internet, we’re at the seven-year itch stage. Not sure what’s going to happen, but we still need/love each other.

Okay wow, if this is issue 1 I'm so excited to see where you go from here! Can't wait to dig in after this quick scan, jaw dropped.

I loved this from start to finish! <3 Can't wait to read it all over again!