Scaffolding: Womb House Books Review

Issue Four: Lauren Elkin on her debut novel, Scaffolding, a new poem by Fariha Róisín, What Jessica Ferri Is Not Reading, and the genius of Shirley Jackson

In the fourth issue of the WHB Review, we are thrilled to speak to Lauren Elkin about her debut novel, Scaffolding, to publish a new poem by Fariha Róisín, and to ruminate on what we aren’t reading. We are looking forward to the October meeting of our book club, when we will celebrate the genius of Shirley Jackson.

Follow us on Instagram and check our website for announcements and events. Thank you for reading and subscribing!

The Question of Inheritance: A Conversation with Lauren Elkin on her debut novel, Scaffolding

I met Lauren Elkin about two million years ago in New York and was immediately struck by her deep intelligence and knowledge of art and culture. Lauren is the author of several books, most recently, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, previously No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian Commute and Flâneuse: Women Walk the City, and she also works as a translator. You can imagine my excitement when I learned that Lauren’s debut novel, Scaffolding, would be published this year, and now, Scaffolding is here. Lauren spoke to the WHB Review about the book from her home in London. —Jessica Ferri

Where did the "glimmer" for this book come from? At the end of the book, it's dated 2007-2023. Did you start writing the book in 2007?

Yes I did! I was in graduate school writing my Ph.D. on Elizabeth Bowen's The House in Paris, and reading Lacan in a grad seminar, and the inkling for this was born at that intersection. Also the building I lived in was being refaced—it was such a thick experience I thought that had to be the premise of a novel. So the structure and some of the concerns (and a few of the character names) comes from Bowen, the preoccupation with desire and lack comes from Lacan, and the rest is just stuff that was preoccupying me to the point of obsession at that point in my life, in my late 20s, curious about how people decided to live their lives together, what made it stick, and what you were supposed to do with all the extra circulating desire.

How does it feel to publish a book that you began writing seventeen years ago?

It's such a relief to have it done and out in the world! I tend to nurse books like some people nurse drinks—Art Monsters was the fastest project from beginning to end and even that took five years. It was a big step for me to just accept what the book was going to be, and what it wasn't, and to let go of it. Ok, five years would be a really long time to nurse a drink.

I'm astounded (as usual) by your total intelligence and knowledge of a subject, in this case, Lacan! Why does Lacan play such an influential (even domineering) role in the characters' lives in this book?

Oh thank you! Well I wanted to write about Lacan but not being a psychoanalyst I thought fiction was the most interesting way to do it. Not as a character, though we do attend his lectures in 1972, but as an intellectual energy, a way of seeing the world. My friends who are Lacanian psychoanalysts really do see everything through the lens of his writing, he is a great philosopher of love and everyday life. But—especially in part two—I also wanted to challenge psychoanalysis and Lacan in particular, these women might be studying him and inspired by him but they definitely don't take everything he says as given, they push back, they question it.

Your work has much to do with a straddling of identity, of nationality and cultural identity. Anna is clearly a feminist, and we have the ongoing real threat of violence towards women and the murder of women in this novel, and yet, she is a Lacanian psychoanalyst. Doesn't Lacan get criticized for being anti-women? How does Lacan fit in with the feminine nature of this book?

There are two relatively conservative Catholic men whose ideas/poetics/aesthetics inform much of this book—Lacan, and the filmmaker Eric Rohmer. But they are both, I would argue, great feminists, genuinely interested in women and their interior lives and their loves and desires. Lacan gets a bad reputation because—ever a provocateur—he said in the 1972-73 seminar that I write about in my book that there is no such thing as woman. But what he meant was that there is no essence of women, no essential femininity, that "woman" is a construct, that everything we think we know about what women are is filtered through language. That's an incredible statement—not a million miles away from Simone de Beauvoir or Judith Butler.

And one of my enduring questions as a critic and a writer—you saw this in Art Monsters—is the question of inheritance, of what we do with the culture we've inherited, which is, for the most part, male culture standing in for culture in general. Women writers and artists have always been there but their work has been considered marginal until fairly recently; they've had to insert themselves into the culture. I've spent 20 years writing about and engaging with that work by women; I've barely written about work by men (with the exception of Georges Perec and a couple of others here and there). But in this novel, which is so much about all the stuff we inherit, physical spaces, hang-ups about our body, ideas about femininity, beauty, and marriage, that it was worth looking at the psychoanalytic inheritance as well, and seeing what we can make of it, what is useful to us, what isn't.

That's part of what Anna is doing when she visits the Freud Museum in London and marvels at all the stuff. Why keep it, why maintain it, why charge people all this money to visit? What are monuments to great men for? What, if anything, do they offer a young bisexual feminist? It's pretty explicit in the scene where Anna and Clémentine go to the National Gallery and look at Holbein's The Ambassadors, and then each rehearse a man's reading of it—John Berger for Clémentine, Lacan for Anna—and then Anna asks herself afterward why they were doing that. How, she wonders, can they learn to really look at art, the world, each other, in a way that isn't filtered through the male gaze?

The scene at the Freud Museum and at the National Gallery are my favorite parts of the novel and I so appreciate your response and aim here, to write women—their art and experience—into the culture. Why did you choose Holbein's "The Ambassadors" as the artwork for that scene?

One of the things I love about that painting is how much is going on in it. It's very much a work that is enhanced by being guided through looking at it—there is so much symbolism encoded within all the different objects, items of clothing, furnishings, and then of course there's that crazy wonky skull at the bottom. But you could also just look at it for hours and lose yourself in the pleasure of its made-ness, the intricacy of the brushwork, the painter's virtuosic skill. For me it's a painting about interpretation itself, like psychoanalysis, but also about epistemology, how we know the things we know, how we interpret the world around us, how we take meaning from it, and also who we turn to to help us make that meaning, to help us understand. I think at the end of the day we get more from letting other people guide us, though there's obviously much pleasure to be had in going it alone.

Were there other psychoanalytic novels that you turned to in writing this book? There were moments where Scaffolding reminded me so much of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook.

Ha! Would you believe I haven't actually read The Golden Notebook? I couldn't get anywhere with it when I tried years ago. Maybe I should try again. I didn't specifically set out to read psychoanalytic novels to write this book but so much of the literature I love is interested in the unconscious and doubling and haunting—André Breton's Nadja, Perec's Things, A Man Asleep, Annie Ernaux's Passion Simple, anything by Deborah Levy, anything by Elizabeth Bowen.

Can you speak about the structure of the book, in terms of the form of short vignettes, some very brief, only one sentence per page? How did this shape form in your process?

It's funny, some of the longer sections were written first, in 2007, and as time goes on and I get more comfortable with myself as a fiction writer, things get more and more fragmented. I wrote a novel before this, which came out in France under the atrocious title Une Année à Venise (not my title) which has an entire section called Mosaico—meant to echo the mosaics in San Marco—so it's something I've been experimenting with for a while.

You published a novel in France that wasn't published here? What is it about? Are there any plans for it to be translated and published in the States?

I did! I wrote it in English, the original title is Floating Cities. It's about an American art history graduate student in Venice, a local boatman, and a bereaved mother, and they all converge around a synagogue hidden in Dorsoduro. It's very much about how and where we choose to build our lives, the materials we use for it, the ways in which we invest in relationships even though we know people are imperfect and have expiration dates on them. I don't know if it will ever come out in English; it's very much an apprentice work.

But the form is very apt for Scaffolding in particular, though, given that so much of the Lacanian theory I'm engaging with is about the unspoken, the idea that when we speak we necessarily misspeak, that our subtext and unconscious are much richer than our utterances, or writings. I'm also playing with Lacan's practice of the variable session—he would sometimes cut his patients off after a minute or two and send them on their way. A session doesn't need to be fifty minutes long to get some good work done. Likewise, a page of a novel doesn't have to be covered in text; it can just be one sentence.

Scaffolding is so grounded in French culture, Lacan being French, the book taking place in Paris, and the characters dealing with, in some cases, the intergenerational trauma of being French, and being Parisian, French-Jewish. I'm wondering, as a person who is American and was raised in America how does your American background and identity shape your interests as a writer?

My relationship status with Americanness is it's complicated. I was born and raised in New York (Long Island) and moved to Paris when I was twenty, and have lived there more or less ever since. That's why I describe myself as Franco-American: I've now lived in France for longer than I lived in the U.S. My everyday language is a blend of French and English, I write and translate in French and in English. I became a writer in France. The kind of work that allowed me to see how I too might become a writer—Perec, Ernaux, Duras—I encountered in French, in France. American writing didn't (doesn't) make it possible for me to write, it made me feel like writing was this other thing that I couldn't (still can't) access.

Lauren Elkin is the author of Art Monsters and Flâneuse, a New York Times Book Review notable book and a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, Le Monde, Frieze, and The Times Literary Supplement, among other publications. A native New Yorker, Elkin lived in Paris for twenty years and now resides in London.

Krakatoa, a poem by Fariha Róisín

Krakatoa

After Meena Alexander

Under the frangipani tree the bulbul sings: My soul knows rivers, Euphrates, Pabna, Nile, Bosphorus, Ganga, like the Ganges, rivers of bhang! I dance against the vivid greens, mountainscape so fresh it looks like Yash Chopra chic, blue cornflower chiffon, stalwart against the wind. The loud hum of urgency swirls louder still as I dip a sliced guava onto a plate of salt the tastebuds puckered and pockmarked with eyes, my mouth on fire, tepid sparks. The smoke rises, fire rages as a tulsi bush clamors, voice of reason and control. The plants have always known better, Gabriel chants louder still, across the burning bush. Thrilling, I think. How such small things can be so mesmerizing. How Walid Daqqa wrote to his wife Sana’a, in jail, alarmed, that even after decades tears rolled down his cheeks at the sight of dew, on morning grass. So much so that it brought him awe. “They target love,” he wrote, the occupation’s obsession with obliterating humanity. His resilience even till cancer excoriated him was that they would never know the profundity of his soul, how love was etched regardless of what & whose freedom was taken. At the heart of him, what was left, despite what they tried to punish, remained faithful to the covenant, to the holy truth. As Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib once said, “Do not despair of the path of truth, even if few follow it.” Daqqa made this into swirling silver Arabic letters delicately drawn on black cloth, decorated with green leaves. There is no position more righteous than a martyr, even Jeanne d’Arc was burnt at the stake. A heretic, revived later as a Saint. Or like Jesus, our prodigal son. We deem those with conviction rebels & anarchists, but society is driven by those who channel despair into divine discipline. * This is not burial, it is a resurrection. Krakatoa wakes. Beauty does not become you when you hold yourself hostage with hate. There is a world where light is utilized & nothing is catastrophic. There is hope for us yet, children of beasts and Godmen. Nothing leaks more imagination than domination. MAKE THE WORLD PROFOUND AGAIN, Oh, wait. It was here all along. Lena Khalaf Tuffaha writes “An olive tree is like an iceberg. “The roots run so deep. what we can see above the ground is nothing compared to what lies beneath.” Fariha Róisín is a multidisciplinary artist, born in Ontario, Canada. She was raised in Sydney, Australia, and is based in Los Angeles, California. As a Muslim queer Bangladeshi, she is interested in the margins, liminality, otherness, and the mercurial nature of being. Her work has pioneered a refreshing and renewed conversation about wellness, contemporary Islam, and queer identities, and has appeared in the New York Times, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Vice, Village Voice, and others.

What I’m Not Reading by Jessica Ferri, owner of Womb House Books

The sheer amount of books I’m not reading as a writer, critic, teacher, parent, and bookseller is quite large. It’s monolithic. I enjoy it. There’s something deeply erotic about knowing that I’ll never read them all.

My method is to acquire as many books as possible. I stack them on shelves, and when shelves fill, on the floor. When I finish reading something, I go to the shelves in my bedroom, where I keep the books I haven’t read, (books I’ve read are stored in my office library) and I make a pile of about twelve titles. Then I sit on the floor, and I go through each book, handling them, smelling them, and usually reading the first paragraph or first page. Several are usually eliminated during this first round, and then I work my way to my next read. Here are several books that have been eliminated in recent rounds.

Wars I Have Seen by Gertrude Stein

Since reading Gertrude and Alice by Janet Malcolm, I have always wanted to read more of Stein’s work, but for whatever reason—I like to blame it on brain damage caused by social media use—I haven’t been able to read any of it! I have this copy of Wars I Have Seen, and I find it fascinating that Stein and Toklas were living in the French countryside as Jewish lesbians during WWII and managed to survive. I’d hope that Wars I Have Seen would shed some light on this mystery . . . but then again, maybe it wouldn’t . . . and perhaps it’s not such a mystery after all.

I purchased this Semiotext(e) edition of Indivisible, a novel by Fanny Howe, some years ago, and it has been sitting on my bookshelf ever since. The back cover copy drew me in: “Indivisible begins when its narrator, Henny, locks her husband in a closet so that she might better discuss things with God.” Sounds great. Also, Howe was married to the civil rights activist Carl Senna, and her daughter is Danzy Senna, who just published a new novel, Colored Television. Quite the literary family.

The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard

I’m embarrassed to admit I have never read The Transit of Venus, or any of Shirley Hazzard’s work, aside from her memoir about Graham Greene, Greene on Capri, which was just as charming as you’d imagine. I get the sense that people who have great taste in novels love this novel, and I hope that I will someday finally get to sit down and read it.

No Clouds of Glory by Marian Engel

About two years ago I finally read Bear by Marian Engel, a novel about a woman who has a love affair with a bear. I just loved that book, and so I ordered as many copies of Engel’s other books, which are all out of print, including this beautiful first edition of her first novel, No Clouds of Glory. Sometimes I think I’ll end up loving a book so much that I’m actually afraid to read it—and I think that’s what’s going on with Engel. I feel as if I don’t have the time or energy to really give this novel the attention it deserves, so I just don’t read it.

Desire in Language by Julia Kristeva

Kristeva feels like a writer that one must read in order to understand anything, and I’ve read plenty of her work in bits and bobs throughout college and afterwards, but I’ve never actually read Desire in Language, published in 1977, in its entirety. It’s my homework that goes undone. Just read the opening to chapter nine, “Motherhood According to Giovanni Bellini.”

“Cells fuse, split, and proliferate: volumes grow, tissues stretch, and body fluids change rhythm . . . Within the body, growing as a graft, indomitable, there is an other. And no one is present, within that simultaneously dual and alien space, to signify what is going on. ‘It happens, but I’m not there.’ ‘I cannot realize it, but it goes on.’ Motherhood’s impossible syllogism.”

Jessica Ferri is a writer and critic and the owner of Womb House Books.

The October WHB Book Club: Shirley Jackson

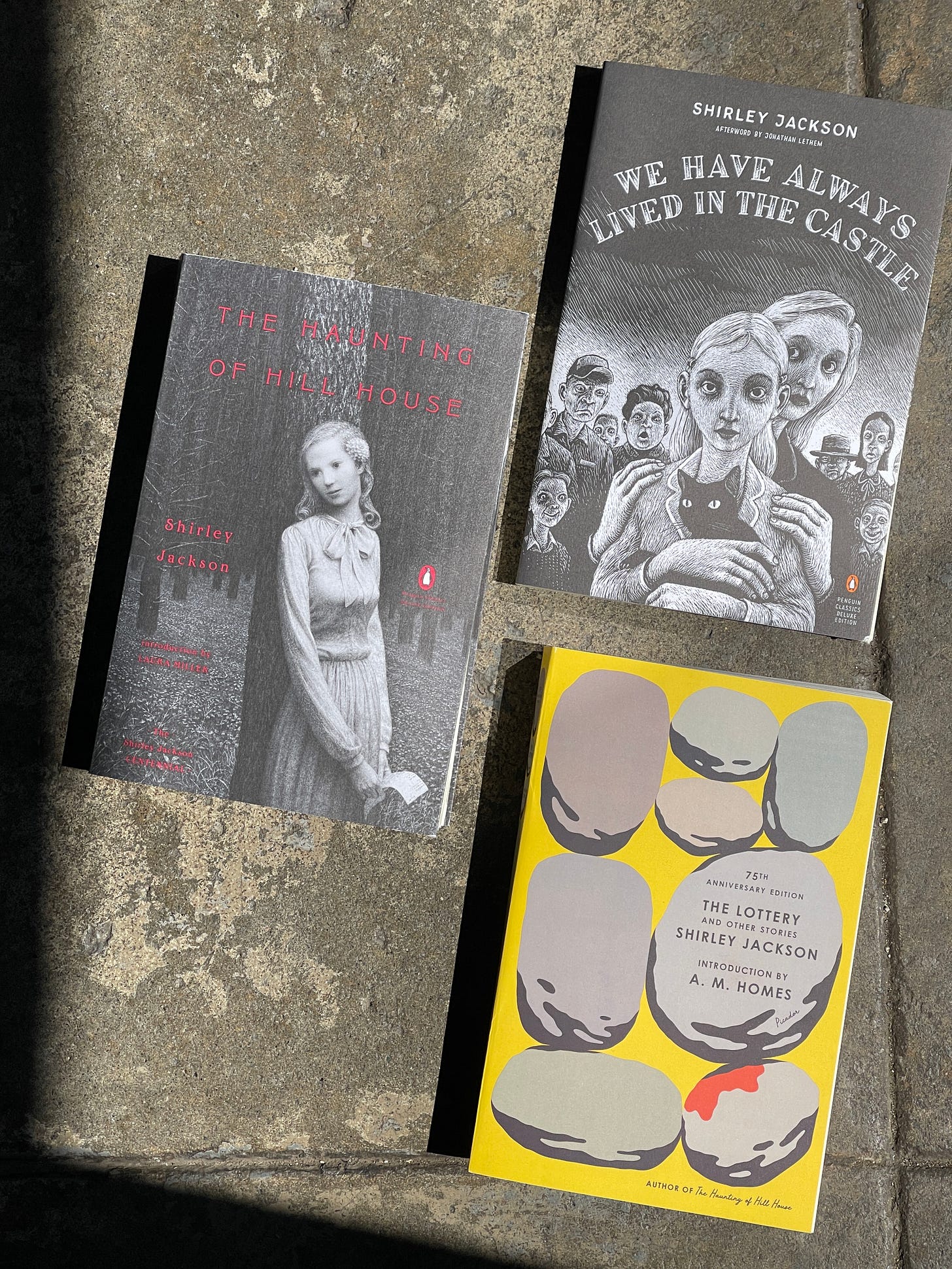

We are thrilled to announce Shirley Jackson as the next pick for the Womb House Books Book Club. In preparation for our next meeting in shop on Thursday, October 17th at 6:30pm, we’ll be reading Jackson’s infamous short story “The Lottery,” and the first chapter of her novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and the fourth chapter of The Haunting of Hill House. All books are available online and in shop. Join us in person or read along in spirit!

Previous book club picks: All Fours by Miranda July, Liars by Sarah Manguso, Monsters by Claire Dederer

As always, stay informed on upcoming events at Womb House Books by visiting us on Instagram or online at www.wombhousebooks.com/events.